Ponting and the 1950s

The leeway traditionally granted to certain kinds of cricketing deception is threatened by the camera's unblinking gaze

Mukul Kesavan

25-Feb-2013

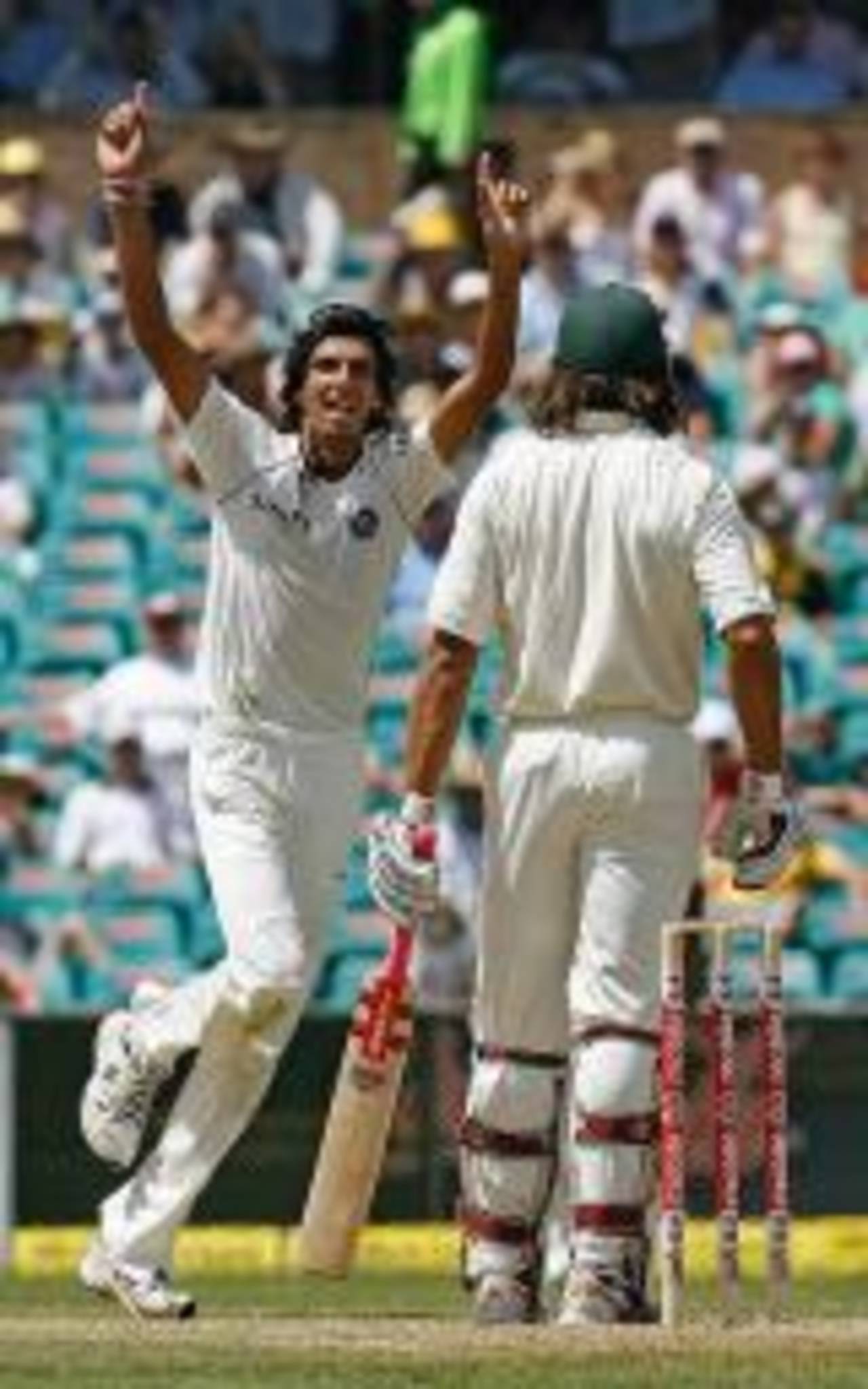

AFP

I met Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi recently at an NDTV India talk show called Muqabla (contest). Before the studio discussion, talk veered to Ricky Ponting's reply to Neil Harvey's withering condemnation of Australian sledging. Ponting had argued that the team's critics and, by implication, their notions of good cricketing behaviour, were stuck in the 1950s, i.e a time when cricket wasn't the professional sport it is today. Pataudi didn't see how that explained anything. "I learnt my cricket in the hardest school there was—at least at the time—the county game. Most of the people I played with were professionals, people who played for a pretty meagre living. Nearly everyone walked, and hardly anyone sledged. There were always one or two people who didn't walk, but they were marked out as cheats."

"There was the one time that I didn't walk," he said, grinning. "We were playing West Zone in the Duleep Trophy and the captain told us not to because the chaps on the other side didn't. So I stood my ground, but that was the only time." Who was the captain? I forgot to ask him. It must have been his Hyderabad skipper, ML Jaisimha.

During the show, a young man in the audience asked if it wasn't natural to retaliate if you were provoked as Harbhajan had been by Symonds. Wasn't it important to speak up, to teach your tormentors a lesson? "A lesson?" asked Pataudi. "Wasn't Harbhajan fined fifty percent of his match fees? You teach someone a lesson when the other man loses his match fees." The studio audience laughed and clapped. He thought Kumble was the only one who had emerged from the controversy with any grace. "He led India to a win in the Perth Test. That was the best possible answer to Sydney, to win on the field of play." Loud applause. Pataudi has a relaxed, ironical manner that makes cricketing chauvinism seem vaguely absurd.

I went up to Syed Kirmani to shake his hand. He was the best Indian wicketkeeper ever and the last one to keep his mouth shut behind the stumps. After him Nayan Mongia inaugurated the age of the cheerleader keeper. Now it's mandatory for a ‘keeper to chirp and yap and appeal non-stop, allegedly to keep his team's spirits up. "After I had played more than eighty Tests, my captain (who shall remain un-named) asked me to appeal more aggressively and frequently. He suggested I imitated another, younger keeper," Kirmani said.

Kirmani refused to name names even off the show, but the the fact that this happened to him late in his career, gives us a clue. I suspect the keeper he was urged to emulate was the young Sadanand Visvanath who was part of the one-day team that won the World Championship of Cricket in Australia in 1985. The way Kirmani told it, he asked his captain with awful calm if he (the captain) had ever felt a lack of support behind the stumps in the dozens of Tests they had played together. If he hadn't, why was he urging him to make dishonest appeals in the autumn of his career? Resounding applause followed this rhetorical flourish.

He told another story of the time he toured Australia. Bob Simpson was the Australian captain. Kirmani thought the umpires in Australia were one-eyed. He'd appeal for an catch, be turned out and Simpson (who was batting) would turn and swear at him. After this happened a few times, Kirmani made his move. He made sure, in between overs, that the umpire was in earshot and confronted Simpson. He began by saying that Simpson was a great man and that he, Kirmani, was a novice nobody so the swearing made no difference to him. On the other hand, being sworn at by a nobody ought to make a difference to someone of Simpson's standing. So Kirmani translated all the desi abuse he knew into English and gave Simpson a earful. The story didn't end there. In a dinner party after the match, Kirmani was talking to Sir Donald Bradman and his wife (or begum as Kirmani put it) when Bob Simpson came up to him and apologized. It's a lovely story and, oddly enough, Simpson comes out of it well: I can think of many senior Indian cricketers who wouldn't have had the grace to acknowledge that they were out of line.

I asked Kirmani and Pataudi when not walking became the rule in Indian cricket. Pataudi was categorical that every batsman in the teams he captained, walked. Both of them thought that the shift came in the Seventies. That seemed about right, anecdotally. I remember Gundappa Vishwanath (debut 1969 with Pataudi as captain) always walked, but Sunil Gavaskar (debut 1971 with Ajit Wadekar as captain) didn't.

There's been a lot of talk about the ethics of not walking, especially after the Sydney Test. Harsha Bhogle raised an interesting question. How could Ponting campaign for the fielder's word to be taken on trust in the matter of a catch, when the same player in his capacity as a batsman was willing to stand his ground knowing he had nicked the ball and been caught. Surely, as Harsha suggested, the player ought to assist the umpire in both cases if he was to remain credible. Ian Chappell (and subsequently, some Australian cricket writers) made the reasonable point that a batsman was merely exercising the accused person's time-honoured legal right not to incriminate himself. The fielder, on the other hand, had the greater responsibility, because claiming a dodgy catch was like perjuring yourself, something that could be severely punished. So it was reasonable to take the fielder's word on trust because the fielder knew that if he was found to have betrayed that trust, sanctions would follow.

But the batsman's right to remain silent is based on the presumption of innocence and that presumption is hard to sustain the presence of cameras. Every time you nick the ball and don't walk, the camera is likely to show you taking advantage of human fallibility. The procedures of law are created in large part to enshrine the benefit of doubt because judges and lawyers know that in a court of law you can't have God as a witness. But today, on a cricket pitch, you can and you do. The television camera's omniscience is beginning to create a crisis for the hard men who refuse to walk.

Behaviour once seen as merely tough or hard-bitten becomes harder to justify when the camera picks up the nick: witness the revulsion that followed Symonds' frank acknowledgement that he had been caught but not given out early in his innings in Sydney. The leeway traditionally granted to certain kinds of cricketing deception is threatened by the camera's unblinking gaze. To his great credit, Adam Gilchrist instinctively understood that batsmen couldn't brazen it out any more and led by example. It's about time that his peers, Australians, Indians and the rest, followed suit. For Pataudi and Kirmani, walking was a point of honour; for cricketers in the age of the camera, it ought to be an act of self-preservation.

Mukul Kesavan is a writer based in New Delhi