CMJ: broadcaster, writer, gentleman

Cricket's greatest friend combined courtesy with a strong sense of authenticity

Ed Smith

17-Apr-2013

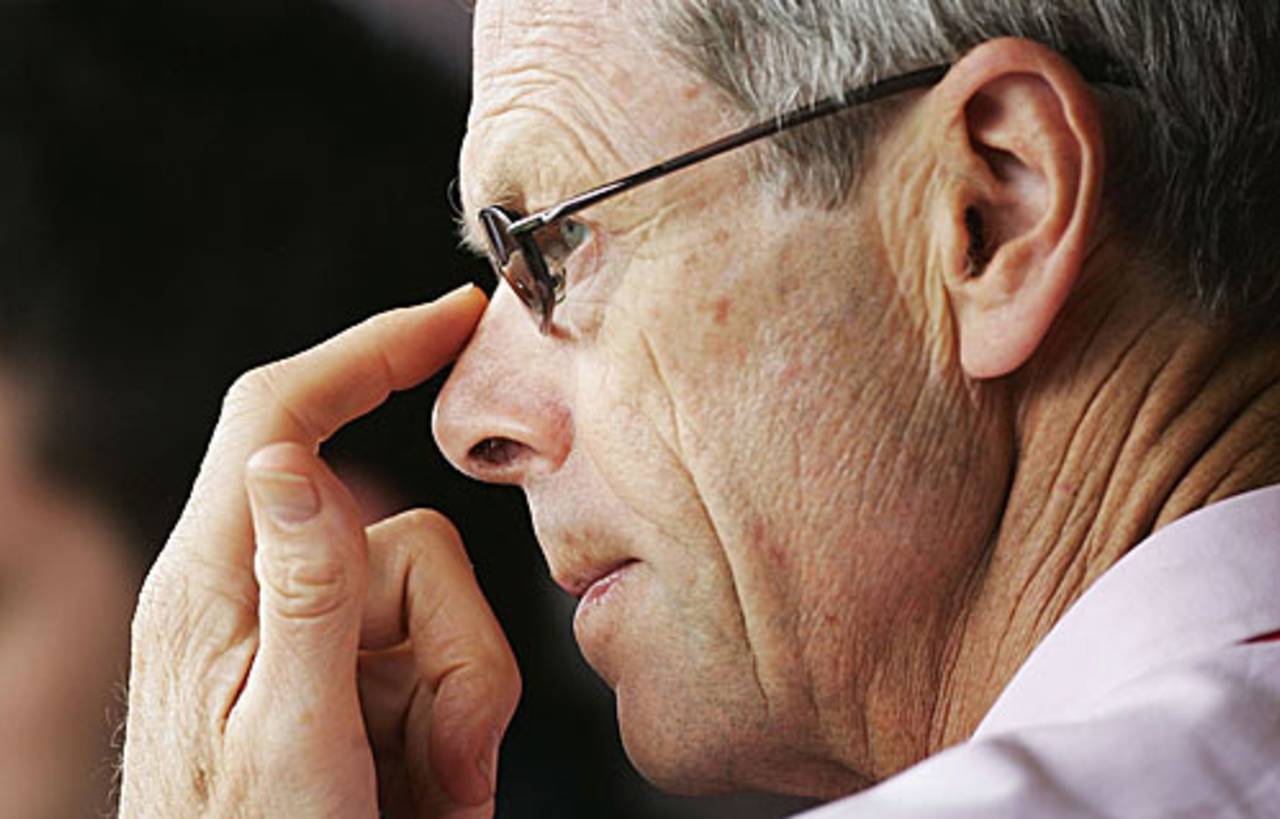

CMJ: a civilising influence • Getty Images

The idea of a gentleman is often mocked but it never dies. When Rahul Dravid retired from cricket, I wrote about the centrality of Dravid's gentlemanliness, how it transmitted itself from the crease to the stands, why the concept was attached to him throughout the cricketing world:

The word is often misunderstood. Gentlemanliness is not mere surface charm - the easy lightness of confident sociability. Far from it: the real gentleman doesn't run around flattering everyone in sight, he makes sure he fulfils his duties and obligations without drawing attention to himself or making a fuss. Gentlemanliness is as much about restraint as it is about appearances. Above all, a gentleman is not only courteous, he is also constant: always the same, whatever the circumstances or the company.

That paragraph applies equally to another gentleman, also a man of cricket, this time a broadcaster and writer rather than a player: Christopher Martin-Jenkins. Yesterday, over 2000 people gathered in St Paul's Cathedral in London for Christopher's memorial service, to mark his death and to celebrate his life.

It was much more than just a cricketing occasion. Among the congregation were leading figures from politics, the media and the Church. Surrounded by the Baroque splendour of one of the world's greatest Anglican cathedrals, we heard poems by AE Housman and John Betjeman - both writers steeped in English landscape and rural life - and sang hymns by Charles Wesley.

It was a social snapshot of a certain strand of Englishness. In 1993, John Major, then prime minister, hoped that "fifty years on from now, Britain will still be the country of long shadows on cricket grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs… and, as George Orwell said, 'Old maids bicycling to holy communion through the morning mist.'" On yesterday's evidence, something of that vision has already survived the first twenty of those fifty years.

ESPNcricinfo is a global site and I realise that some readers will not know Christopher's work. So let me describe the qualities that ran through his print journalism, mostly for the Daily Telegraph and the Times, and his broadcasting, where he was a much loved voice on the BBC's Test Match Special.

Some people have a civilising influence on everything they touch. Christopher was one of those people. His careful use of language, his unfailing courtesy, his determination to look for the good, his reluctance to turn the knife - colleagues, listeners and readers absorbed these things subconsciously, both on the page and over the airways. Above all, despite his great inside knowledge, Christopher retained the freshness of the enthusiast. The job never became just "a job".

"He was cricket's greatest friend," as his colleague Mike Selvey put it. It was a friendship based on love. But to say that Christopher "loved" cricket needs to be expanded. The word is thrown around too lightly. We love this, we love that, we come and go with our loves. Christopher not only loved cricket, he revered it. He took a deep interest in cricket, as a loving parent would care about the well-being of a child. And he cared for every aspect of the game, as though cricketers of all abilities still belonged to the same tradition, the same family. He cared about the game's grassroots as much as about World Cups and iconic series. He hated the idea that the game was just a pyramid of excellence, for which the sole justification was the cultivation of a highly paid professional elite. Cricket was an end in itself, a strand of the human condition, perhaps even an ennobling one.

Christopher knew that beauty was central to the magic of cricket. In its expressiveness and subtlety, cricket can touch the arts more frequently than most sports. Sir Tim Rice's tribute recalled that Christopher's favourite player was Tom Graveney, who made over 100 first-class hundreds for Gloucestershire, Worcestershire and England. Rather than brute force or mechanical efficiency, Graveney batted with elegance and grace - qualities Christopher looked out for throughout his career describing the game.

He hated the idea that the game was just a pyramid of excellence, for which the sole justification was the cultivation of a highly paid professional elite. Cricket was an end in itself, a strand of the human condition, perhaps even an ennobling one

Another tribute singled out Christopher's natural courtesy and manners. Those qualities were integral to his radio commentary - the patience with which he dealt with colleagues, the attentiveness he paid to the game. He did not use charm to pursue his own agenda; his manners allowed those around him to pursue theirs.

Courtesy coexisted with a strong sense of authenticity. Christopher never said or did anything remotely phoney, and that goes a long way to explaining why he connected with people, why he enhanced their enjoyment of cricket. He would not have touched so many readers and listeners if he had tried to adopt the common touch or artificially dumbed down. He stayed true to himself, without hinting at caricature. His career showed that you do not "connect" with people by aping demotic tastes. You merely demean yourself.

During the service, a recording was played of some of the greatest moments of Christopher's radio commentary, spread across his 50-year career. In a few seconds, we heard his voice mellow and soften with several decades' experience of cricket and life.

For me, hearing that famous voice once again was the most moving moment. So many memories, so instantly recalled. Christopher described the sense of hope and optimism that greeted the first Test hundred by a 17-year-old prodigy called Sachin Tendulkar. He captured the anxious thrill of listening to Kevin Pietersen's counter-attacking hundred at The Oval that secured the Ashes in 2005.

Listening again, I remembered where I was at each moment, reflected how deeply cricket is intertwined with other aspects of life. The warmth of summer memories, the happiness and sense of security that cricket brings, washed over me. Nostalgia? Perhaps. But nostalgia, too, is a form of reverence for the past.

As cricket celebrated the life of a gentleman yesterday, I reflected on a final irony. It is very rare, in this age of professionalism and self-promotion, to hear much about the ideal of gentility. And yet so many people, of all backgrounds, instinctively know a gentleman when they see one - or even when they just hear him speak on the radio.