India's rock of ages

Big-match batsman, tireless bowler, agile fielder, dependable team man - Vinoo Mankad, who was born 100 years ago today, was the driving force behind the India team of his era

Haresh Pandya

12-Apr-2017

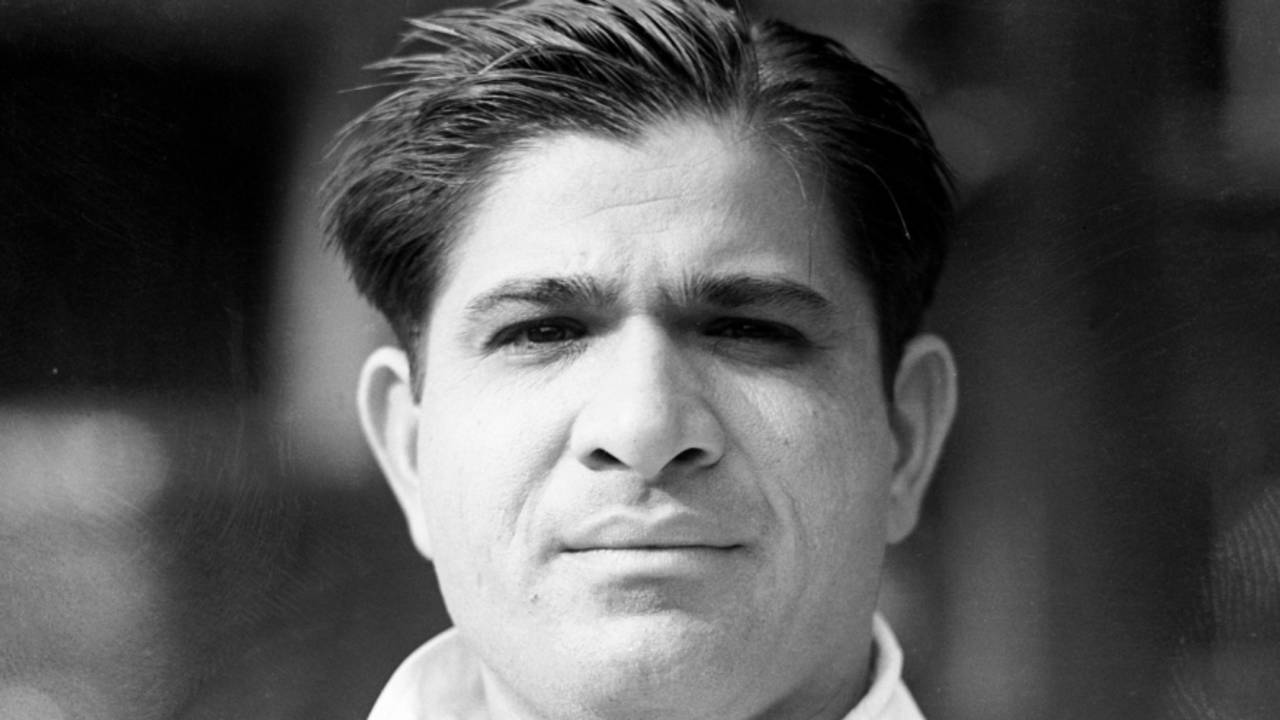

Mankad shouldered most of the national team's burden throughout his Test career • PA Photos

A perfect team man. This is how one might describe Vinoo Mankad, one of the truly great allrounders of all time. As a key member of the India team in the late 1940s and much of the 1950s, he was always in the game, and more often than not in any given game, contributing in some way or the other, mostly on a grand scale.

India did not have too many world-class players in those years, when drawing a Test against any opponent, including the then lowly New Zealand and Pakistan, was considered an achievement. The national side, almost invariably lacking in genuine talent and confidence, depended heavily on Mankad, and whenever it took the field without him, it appeared to be a listless unit.

As an orthodox left-arm spinner in the classical mould, a plucky right-hand batsman and an agile fielder, particularly off his own bowling, Mankad had few peers and no superiors in the world throughout his chequered yet eventful Test career, the start of which was delayed by World War II.

Mankad was often hailed as the Keith Miller of India. But unlike the dashing Australian allrounder, he was fated to represent an eternally weak team and had to be a relentless workhorse while carrying the additional weight of the nation's expectations. He batted at every position in Test cricket, not by choice but because of circumstances.

The national side, almost invariably lacking in genuine talent and confidence, depended heavily on Mankad, and whenever it took the field without him, it appeared to be a listless unit

Probably no cricketer in the history of Test cricket has ever turned in a single performance as heroic as that of Mankad at Lord's in June 1952. He was not in the original Indian team, as he was bound by a lucrative contract with Haslingden in the Lancashire League, and had made himself unavailable for the country.

Mankad had written to the BCCI in November 1951, asking, rather unnecessarily, for guarantee of selection in the Indian team for the tour to England. When a reluctant board did not entertain his demand, Mankad wrote to Haslingden saying that he was available for them for the entire season.

Consequently, he was not picked, with the chairman of the selection committee, CK Nayudu, saying Mankad's unavailability was "not a great loss". (And to think Mankad had played a pivotal role in bringing India their maiden Test triumph only a few months before.)

Come the first Test, at Headingley, where the hosts handed Vijay Hazare and company a humiliating defeat by seven wickets in four days, and it became obvious that Mankad's absence was indeed a "great loss". This was the Test in which India lost their first four wickets without a run on the board in the second innings.

It became clearer that only Mankad could lift the morale of the despondent players in such a situation. Manager Pankaj Gupta swung into action, convinced the BCCI that Mankad was the need of the hour, and started negotiations with Haslingden to bargain for the allrounder's release.

Mankad bats at Lord's in 1952. The match came to be known as "Mankad's Test" for his stellar contributions with bat and ball•PA Photos

Initially they agreed to release Mankad only for the second Test, at Lord's. But they gave in after plenty of persuasion and reluctantly released their star recruit for all three remaining Tests.

Coming straight from league cricket and without having played any first-class cricket in England that season, the 35-year-old Mankad was pitchforked into the playing XI at Lord's. Expectations were higher than ever before.

Hazare won the toss and asked Mankad to open the Indian innings with Pankaj Roy. Dark memories of being 0 for 4 at one stage in the previous Test were still haunting the team. However, England soon realised they were up against a competitive cricketer of class, as Mankad faced Fred Trueman and Alec Bedser with aplomb, adding 106 with Roy, before being first out for a masterly 72 - the top score in the innings - in a little under two and a half hours.

Despite such a solid start, the entire team was bundled out for 235 shortly before the close of play on the opening day. During England's massive first innings of 537, which lasted over a day and a half, Mankad bowled 73 overs, (24 of them maidens) and claimed 5 for 196.

As if that were not enough, he opened the Indian second innings, after having bowled 31 overs on day three, without showing any sign of fatigue, and was undefeated on 86, out of India's score of 137 for 2 at stumps.

Come the first Test at Headingley in 1952, where the hosts handed India a humiliating defeat by seven wickets in four days, it became obvious that Mankad's absence was a great loss

With the stonewalling Hazare for company, Mankad simply tore into the English attack thereafter. When sheer exhaustion did him in and he missed a full toss from Jim Laker to be bowled for a superlative 184, Mankad had salvaged much of India's pride, although defeat was still unavoidable.

He was the third batsman out, with the score at 270, and India were eventually bowled out for 378. Though wicketless in England's modest second-innings chase, Mankad bowled 24 overs, half of them maidens, and gave away less than a run and a half per. In all, he was on the field for nearly 17 out of 25 hours of play.

"England won by eight wickets, but Mankad's performance must surely rank as the greatest ever done in a Test by a member of the losing side," noted Wisden. Unsurprisingly, in a glowing tribute to his tour de force, the 1952 Lord's Test has come to be known as "Mankad's Test" or "Mankad versus England".

****

Mulvantrai Himmatlal Mankad, affectionately called Minu at home but universally known by his sobriquet of Vinoo from his schooldays, was born on April 12, 1917, in the erstwhile princely state of Jamnagar (previously called Nawanagar) in Gujarat.

Though there were no sportspeople in his family, Mankad appeared destined to carry forward Jamnagar's rich cricket legacy, considering his natural talent for cricket, which was apparent from a very early age. He grew up in Jamnagar hearing about the exploits of sons of the soil, ssuch as KS Ranjitsinhji and KS Duleepsinhji, as well as Amar Singh and L Ramji.

Mankad's talent blossomed at Nawanagar High School under SMH Colah, one of the few Parsee cricketers to play for India, who played for Nawanagar at the time and served as a coach at Nawanagar High School. A brilliant fielder, Colah emphasised the value of good fielding, in particular while teaching the basics of cricket to Mankad.

Mankad's batting evolved under the mentorship of Duleepsinhji•PA Photos

At times Mankad would receive tips from Duleepsinhji and other Indian and English cricketers who were part of the great Nawanagar team, especially Bert Wensley, the former Sussex allrounder. While Duleep moulded Mankad the batsman, Wensley dissuaded him from bowing medium-fast and advised him to perfect orthodox left-arm spin, which seemed to come to him naturally.

Though most of those, including Arthur Gilligan, who saw Mankad were in awe of his genius and predicted a bright future, he made an unspectacular first-class debut, against Jack Ryder's Australian side in 1935. He was equally unimpressive in his first Ranji Trophy match, for Western India in 1935-36 - he failed to take a single wicket and remained unbeaten on 0 batting at No. 11.

The next season, playing for the newly constituted Nawanagar side, led by Wensley, he put up a far better show, including 185 in the final against Bengal, and contributed substantially to his team's victory in the Ranji Trophy. Surprisingly, when Lord Tennyson's team came to India in 1937-38, Mankad's name was missing from the first unofficial "Test" in Lahore.

A determined Mankad responded by scoring 62 and 67 not out as an opener and taking 4 for 53 and 2 for 56 as Jam Saheb of Nawanagar XI beat the visitors by 34 runs in a first-class match at Ajitsinhji Ground in Jamnagar.

Included in the Indian team for the second "Test" in Mumbai, he responded by scoring 38 and 88 and taking the wickets of Tennyson and Arthur Wellard for figures of 2-1-6-2 in the first innings. He continued to impress in the remaining three "Tests" in Calcutta, Chennai and Mumbai and headed both the bowling (15 wickets at 14.53) and batting (376 runs at 62.66) averages. Tennyson stated that Mankad would walk into a world XI.

While Duleep moulded Mankad the batsman, Wensley dissuaded him from bowing medium-fast and advised him to perfect orthodox left-arm spin

The best years of Mankad's youth were lost due to World War II, when he was ready for the serious business of Test cricket, though he continued to excel, and impress, in the Ranji Trophy and Pentangular tournaments in that period. In 1945 he toured Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) with a representative India side and returned figures of 8 for 35 and 2 for 83 in the only first-class match against All-Ceylon in Colombo.

He bowled equally well against the Australian Services Team the same year and reaped a rich harvest of wickets. "With Hedley Verity gone, I don't think there is a better left-hander than Mankad," said the Australia captain Lindsay Hassett. "I'm sure he will do well on India's upcoming tour to England."

It was not before he was 29 that Mankad made his maiden Test appearance, at Lord's, scoring 14 and 63, looking "capable of demoralising England bowling" according to Wisden. He bowled 48 overs in England's first innings of 428 and took 2 for 107. He excelled more as a bowler in the remaining two Tests at Old Trafford and The Oval.

Despite playing for an India side weaker in bowling and poorer in fielding than their opponents, Mankad shone brightly that the English summer. With 129 wickets and 1120 runs, he completed the allrounder's dream "double" and was chosen by Wisden as one of its Five Cricketers of the Year.

All too often, Mankad was used as a workhorse with the ball•The Cricketer International

Like many slow left-arm spinners before and after him, Mankad had a tough time against a star-studded batting line-up headed by Don Bradman in Australia in 1947-48. His 12 wickets came at 52.50 each, after he carried the load of the bowling in almost all the five Tests.

Also, he had difficulty opening the innings against Ray Lindwall in particular. So much so that he was out to Lindwall six times, three of those for zero. However, he did hit bristling hundreds in the third (116) and fifth (111) Tests in Melbourne, albeit after being advised by Lindwall himself to reduce his backlift.

It was in this series that Mankad, "in the act of delivering the ball", ran out Bill Brown, who was backing up out of his crease far too early in the second Test in Sydney. Earlier, too, he had dismissed Brown in an identical fashion in India's tour match against an Australian XI, led by Bradman, at the same venue.

When his sportsmanship was questioned in many quarters, Mankad found a supporter in none other than Bradman, who said Mankad was "so scrupulously fair that he first of all warned Brown before taking any action". The term "mankad" (verb) has since become a part of cricket's lexicon to describe the act of effecting such a dismissal.

"With Hedley Verity gone, I don't think there is a better left-hander than Mankad"Lindsay Hassett, captain of Australia

A willing workhorse, Mankad was called upon to bowl marathon spells right from his first Test. His 17 wickets in the five-Test home series against West Indies in 1948-49 were earned at a higher cost after gruelling work on the field, which included spells of 59 overs in Delhi and 75 in Mumbai.

He seemed to be such a tired player by the end of the rubber that his form fell right away. There was a noticeable decline in his performance, both with ball and bat, in the two series against the Commonwealth teams, and his returns were a mixed bag. However, his 12 wickets in the last two "Tests" against the second Commonwealth team were a welcome relief.

Mankad the bowler was at his devastating best against a below-strength England in 1951-52, taking 34 wickets at 16.79, an Indian record for the most wickets in a series, broken by BS Chandrasekhar 20 years later.

Not only did he author India's maiden win in the heavyweight division of cricket, in the fifth Test in Madras, by taking 8 for 55 and 4 for 53, but he also scored 230 runs in the series to enhance his reputation as a champion allrounder.

Barely two months after his Herculean performance at Lord's, Mankad demolished Pakistan in the first Test in Delhi. His dream figures of 47-27-52-8 and 24.2-3-79-5 went a long way towards India registering their first ever innings victory in Tests. But Pakistan made the most of Mankad's absence from the second Test, in Lucknow, and beat India by an innings.

Pankaj Roy and Mankad walk back in to resume their record 413-run opening stand in Madras•Wisden Cricket Monthly

He returned for the crucial third Test, in Mumbai, in a grand manner: while helping India win by ten wickets with figures of 3 for 52 and 5 for 72, as well as scoring 41 and 35 not out, he became the quickest to bring up the double of 100 wickets and 1000 runs, in only his 23rd Test - a world record that Ian Botham broke 27 years later.

At 36, Mankad was fairly impressive, if not spectacular, in the West Indies in 1952-53. Notwithstanding the emergence and success of legspinner Subhash Gupte, he bowled 345 overs, including 82 in the first innings in Kingston, and bagged 15 costly wickets. His hard-hitting knocks of 96 and 66 went down well with Caribbean cricket enthusiasts.

Mankad gave yet more proof of his prodigious gifts when, at 39, he scored two double-hundreds (223 in Mumbai and 231 in Madras) in four Tests against New Zealand in 1955-56. In fact, he and Roy put on a world-record opening partnership of 413 in Madras. (He also took 4 for 65 in 45 overs in the second innings.)

Though not unimpressive, Mankad's career statistics of 162 wickets at 32.32 and 2109 runs at 31.47 in 44 Tests hardly reveal his true genius. As a bowler, he was overbowled at times. As a batsman, his changeable place in the batting order and the considerable pressure under which he often played may have affected his output.

Mankad died in 1978, the year that saw the rise of Kapil Dev, another great allrounder, but, all things considered, not quite Mankad's equal. Both in talent and achievements, as well as the circumstances in which they played, they were poles apart and beyond comparison.

Haresh Pandya is a freelance journalist, specialising in cricket. He has written for many leading publications, including the New York Times, the Guardian and Wisden