'In a democracy, the majority always rules'

His commercial savvy saved cricket from bankruptcy; now they say cricket needs saving from his lust for power. To Jagmohan Dalmiya, though, the idea of a split in world cricket is laughable

Sambit Bal

20-Sep-2015

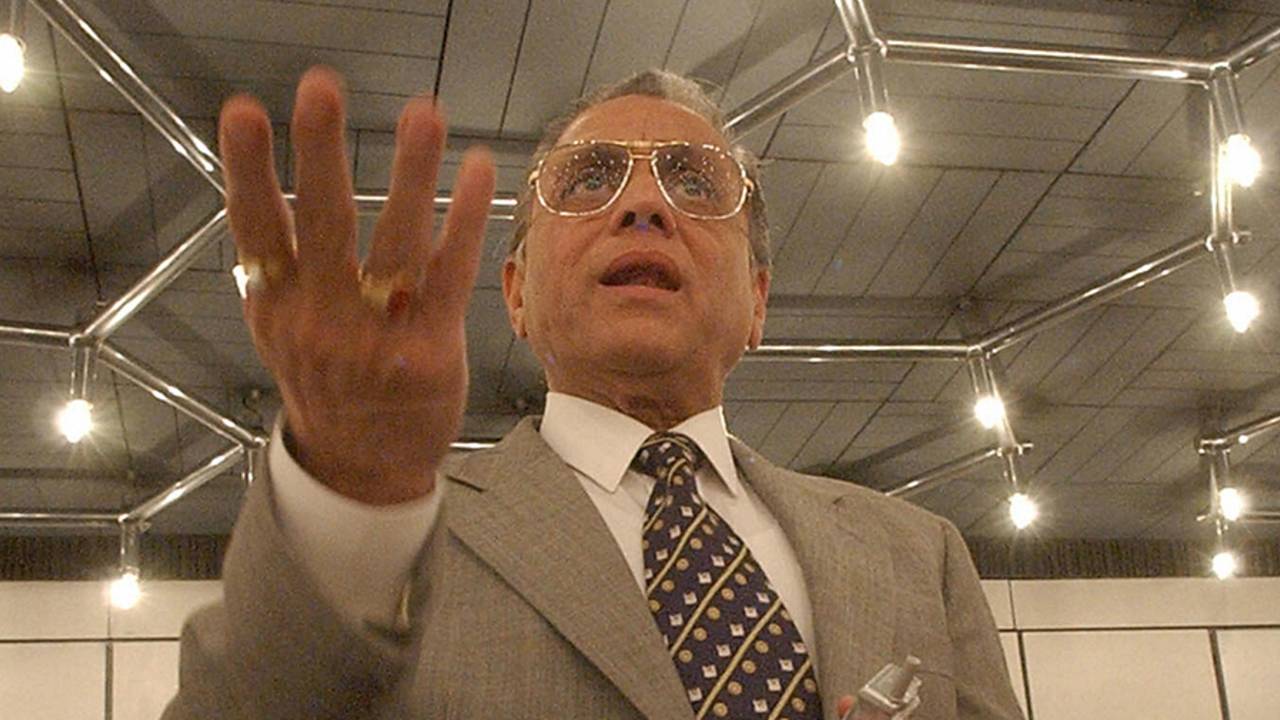

'Players always share their problems with me, confide in me, and I do my best to solve their problems' • AFP

Behind Jagmohan Dalmiya's desk in his Shakespeare Sarani office in South Kolkata, from where he controls Indian cricket and moves and shakes world cricket, two large photographs capture his happiest memories as president of the ICC. In one, he is a beatific picture of fulfilment, declaring the 1999 World Cup open, flanked by Tony Blair, the British Prime Minister, Ian McLaurin, the then chairman of the English cricket board, and Tony Lewis, in his capacity as television presenter. In the other, he looks just as pleased, as Steve Waugh accepts the World Cup trophy from him.

In an ironic, but perhaps inevitable, twist of events, he now finds himself in a confrontation with the ICC, which, in theory at least, could lead to India being suspended from international cricket. There is a lot you can ask Dalmiya, but the delicate nature of his job restricts him to saying a lot less than he can. Given the constraints, he is as candid as he can be.

You are nearing the completion of your second term in a significant administrative role at the BCCI. How much has cricket changed between when you started and now? How differently is the game run now?

When I became secretary, in 1993, the board had a deficit of Rs 85 lakh. In 1987, India hosted the World Cup. That year we made a loss of Rs 7 lakh. There was money in cricket, but it was not coming to the board. Doordarshan would tell us to count ourselves lucky that they were telecasting the matches. They were even demanding Rs 5 lakh to telecast a match in 1993. In that context, the Supreme Court judgment which upheld the board's right to the events was historic. Once we managed to convince the court that we were the producers of the cricket telecast, we haven't looked back. I still remember the night when the judgement was delivered - at Justice Varma's residence at 12.30. I would say it changed the face of Indian cricket.

There is a perception that this time you want to leave a legacy bigger than that of a money-man.

I don't know where this comes from. I have always worked according to the need of the hour. When I came in first, money was a problem, so we had to make sure money came in. This time, the challenge was different. Our team was rotting at the bottom of the pile in international cricket. Our reserves bench was empty though, ironically, talent wasn't a problem: we were champions at all levels of cricket, except Test. Obviously, something was going wrong between ages 19 and 21.

So how did you approach your task this time?

I came with both an open mind and a closed mind. I was open to any new ideas that could revitalise Indian cricket. But a closed mind because I thought it was futile employing two foreigners as coach and trainer if nothing was getting better. I could understand aging players getting injured, not so many young ones. But after I met [John] Wright and [Andrew] Leipus, I not only decided to retain them, but added one more [Adrian le Roux] to the team.

What changed your mind?

I came hard at them. I told Wright that I respected him as a former international player and captain, but we were paying good money and we wanted to see results. There had to be accountability.

Leipus told me that I was free to throw him out, but that we must understand the injuries first. Not a single player who had been with the team for a period of time had got injured, he said. It was the new guys who were breaking down, often after three days of physical training, because they were basically so unfit when they came in.

Wright pointed at flaws in the selection policy. We were selecting boys on the basis of their domestic performance, but were not giving them time to settle down in international cricket. Two or three failures and the new boy was out and another came it. It was up to the board to find a solution. Their arguments were valid and they opened my eyes.

But apart from retaining them, what did you do to address the issues they raised?

I realised that our fitness culture had to change, and change at a lower level. We have done a lot to address that. Gymnasiums have been set up at state level and at organisations like the National Cricket Academy and the Cricket Club of India. We have hired physical trainers and we are training them to become cricket trainers. That will be another job for Leipus and Le Roux. After all, we can't keep hiring foreigners. We might bring in another foreign trainer for our academy, who will then train all the zonal trainers. Things have begun to happen, but it will take time … one year, two years.

How did you address John Wright's problem of selection?

This was a trickier issue. As an administrator, I have always believed in leaving the specialised jobs to the specialists. Selection is certainly a job for the specialists but it is up to the administrators to organise the cricket calendar. I realised that international exposure was vital for our domestic cricketers.

We now have two teams coming in from abroad every year, and two of our teams going out. To be a strong international team, we had to have a strong reserve bench. And to have a bench of 30 players, you had to expose 100. A tours and under-19 tours are crucial. You can see the results now. Yuvraj [Singh], [Mohammad] Kaif, [Ashish] Nehra, Parthiv [Patel] are all products of A tours. Now we have got [Avishkar] Salvi, [Gautam] Gambhir, Amit Mishra, Aakash Chopra, and another real star in the making, [Ambati] Rayudu. Our reserve bench is overflowing.

I was criticised for sending teams out during our domestic season, and they had a point. But this is something I didn't want to leave to experts. I know that our domestic cricket needs strengthening, but my first task was to make the Indian team strong. We are making every effort to improve our pitches, but it will take time. Wankhede will not become Perth overnight. So the only option right now is to send our boys abroad. Meanwhile, we are doing what we can to make our domestic cricket competitive.

As for selection, I don't interfere with the process. But the selectors know that they are accountable. I never ask them to pick anyone, but I can always ask why they picked someone.

The change in the Ranji Trophy format has been welcomed. But there is a feeling that the new Duleep Trophy format has made the tournament completely irrelevant. Elite A v Plate B, who cares?

The criticism is valid. But change was needed because everybody agreed that the Duleep Trophy had become totally lacklustre. There was a rationale behind the current format. It was devised to give players from the Plate division a chance to show their talent. But if it has not worked, we will have to look at it again.

People still talk about the glory days of the Pentangular, how fierce the competition was between the Hindus and Muslims and Parsees. Perhaps we need to recreate that kind of rivalry again, not through communities but zones. There is a feeling that the zonal system is the last evil in Indian cricket, but it does have its merits. Maybe for the Duleep Trophy, going back to the zones is the answer.

Another reform that seems to have got stalled is the professional contract system for the players.

It's not stalled at all. It's just that we don't want to do anything unilaterally. I had a discussion with the boys, and I asked them whether they would like it introduced immediately or later. I wanted a percentage fixed. The Australian board was the one that gave the highest share of its earnings to the players: 25 per cent. So we decided on 26. Of course, the percentage is a misnomer because it has nothing to do with the actual earnings. But just to make everyone happy, we fixed a percentage. My major concern was that first-class players should also benefit. So it was decided that 13 per cent would go to the international players and 13 per cent to the domestic players. We want to make sure that a first-class cricketer can play up to seven or eight years and go with a good sum. First-class cricket needs to become a career.

We are working out the details - expect it to be finalised with in two to three months. We want to build a system where an infrastructure will be in place to manage the players' money.

Are you in favour of an employee-employer relationship between the board and the players?

The problem with an employee-employer relationship is that the employer is superior. In our case, the board and the players are both equal pillars. I have always believed that the relationship should be equal. There is so much talk about players versus administrators. I have never seen it that way. Players always share their problems with me, confide in me, and I do my best to solve their problems.

This certainly didn't seem the case at the time of the contracts crisis, during the ICC Champions Trophy. The players felt quite hard done for by the board.

That's an absolute misnomer. And the media made too much of it. It was suggested that I changed my stance before and after the ICC trophy, which is completely untrue. What I said to the players before the ICC Trophy was that the ICC had entered into a contract till 2007, in which there were some clauses that were causing concern - these clauses were not there earlier - and they are giving it to us in writing that these clauses will be reviewed and we should go and play the tournament.

Are you are going on record to say that the clauses about image rights were not in the original draft?

Absolutely. The clauses were not there. I was president [of the ICC] at the time; they were inserted later. I said to the players that the clauses are improper, but play this tournament and I will get them changed. I never supported the clauses.

The other thing that hasn't been understood is that there were two kinds of Playing Nations' Agreement (PNA). For the Champions Trophy, it was that you selected a team from the eligible players [the ones who had signed the contract], and thereafter, till 2007, it was that you selected a team and then got the players' consent. If we had failed to send a team to Sri Lanka, India would have been suspended. I couldn't have taken that risk.

Did you seriously believe that India could be suspended?

Yes. India can be suspended even now. That's what Malcolm Gray is saying even now. There is correspondence going on between us and the ICC over this, which I can't share with you. It's another matter that we have our clout and that we have our votes. But at that time people were pleading with us, saying don't get us to vote, because we will have to vote against you. When the matter of arbitration came to vote, I was isolated. I had never lost an election in my life before, but I lost 12-1 then. It was a simple case of them protecting the interests of their boards. They couldn't have made their boards liable against any future claims. The New Zealand board, in fact, wanted to move a motion to suspend the Indian players, but I stalled it on the ground that they had to give notice for such a motion and not move it on the floor.

I kept telling the players to have faith in the board and in my administrative abilities. They were being misguided by the FICA (Federation of International Cricketers' Associations) and by certain former players. Finally, what happened? FICA ran away. It's the board that stood behind the players.

Coming back to the ICC contract: the Indian board was clearly a party to it, having signed the PNA.

There were three agreements. The first one, which was signed earlier, specified that the member boards would have to abide by whatever the ICC committed to the sponsors. Then came the PNAs, which we signed with certain objections. We said certain clauses were against the fundamental rights of the players and we doubt very much that they would stand up in a court of law. They said that we would have to sign unconditionally because of the earlier contract. We said that we had signed the contract on the basis of certain commitments [to sponsors] which had been agreed previously, but you can't keep making commitments on our behalf and expecting us to fulfill them.

So where does the matter stand now?

We will deal with it when it comes up. I believe we have a good case legally.

There is a perception that much of the bad blood between the ICC and the BCCI is due to personal animosity. Malcolm Gray and Jagmohan Dalmiya aren't the best of friends.

There is no question of personal animosity. We fought an election once and he lost it fair and square. As administrators, you don't have to be best friends, but you need to have good working relationships, which I have had with everyone, including Gray. When I became ICC president, we had 16,000 pounds. When I left, it had increased to 17 million, and we achieved that by working together. As BCCI President, how can I have anything against the ICC? We are part of it. It is our own body.

There is a great fear, particularly in the English and Australian establishments, that Jagmohan Dalmiya's ultimate agenda is to split world cricket.

This is either mischievous or plain ignorant. In a democracy nothing splits - the majority rules, as it should. If people don't like the majority opinion, that's too bad. But to say that the ICC will split is outrageous.

Perhaps only the power centres change.

Of course, that is the rule of democracy.

You must be looking forward to Ehsan Mani taking over as ICC president.

Yes. He is an intelligent, experienced and able administrator. We have worked together before and I am looking forward to working with him again.

Questions hang over the formation of an organisation like the Asian Cricket Council (ACC). What is it if not an overt effort to create a power bloc?

The ACC has been in existence for a long time now, and you shouldn't forget the positive contribution it has made towards globalisation. I have always been a proponent of globalisation and I remember when I brought up the subject at an ICC meeting years ago, somebody pointed out that as secretary of the ACC I should be doing something about spreading cricket in Asia, which I thought was a very valid point. Asia had only five associate members then. There was Bangladesh, UAE, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore. Since we started working on it, we have brought in Nepal, Bhutan, Maldives, Brunei, Thailand … from five to 14 within one year.

Globalisation, it is said, is a euphemism for expanding Dalmiya's vote bank. Granting Test status to Bangladesh would seem to be a case in point.

At the moment, Bangladesh may not be playing that well. But what they need is international exposure; they need to play with better countries, get used to competing. New Zealand took 23 years to win their first Test match and the lowest Test innings score still stands against them. India took 20 years. Zimbabwe struggled a lot. So give Bangladesh time.

When people point fingers at me, they should not forget that Bangladesh was given Test status unanimously … England, Australia, all voted in favour.

But what about the vote bank theory?

It's absolutely cynical. How do you expand your vote bank by bringing in new countries? New countries come in as affiliate members, without a vote. They are promoted as associate members only when they prove themselves, and then they have half-a-vote.

But can cricket really take root in countries outside the Commonwealth, or without Asian expatriates?

Commonwealth is not the issue. Yes, to an extent, expatriates have been responsible for the growth of the game. But a lot of local people are embracing the game too. Japan is a member now, and they have a team full of Japanese players.

There was this experience in Singapore, where cricket used to be banned in schools because the government thought it was a waste of time. After the 1996, World Cup, we organised a triangular tournament in Singapore, between India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka and requested the Prime Minister to come. With great reluctance he agreed to come for five minutes. But he stayed on for three hours, had lunch with us and granted 16 acres of land near Changi Airport for a new stadium. Needless to say, the ban was lifted.

There are so many experiences like this that convince me that cricket can be a global sport. We have to take it to people, explain it to them, get them to play and it will take root.

Accountability has been a buzzword for your current tenure. But we are not very clear about how the board spends its the money.

Good you asked. I would have brought it up even if you hadn't. It's not that we are not transparent, but perhaps suo moto transparency is the need of the hour. Our balance sheet is a public document. But I want to publish our accounts, not in accountant's language, but in language that everybody can understand. A lot of writing happens in the media about the board's functioning and a lot of it is due to ignorance. Do you know that the total administrative costs of the board don't exceed five per cent of its earnings, and that we have fixed a cap at 10 per cent? A lot of developmental work is going on, and I would like people to know how the board spends its money.

For all the reforms that have been initiated in other areas, the BCCI is still run the same old way. Cricket is a fully professional sport now, yet it is not run by professionals.

It depends on what you mean by professionals. Sports administration is not taught in any management school. Do you mean an MBA or a Chartered Accountant would do a better job than the current administrators?

Why can't cricket have paid executives? Indian cricket is rich enough to pay Jagmohan Dalmiya a salary.

In no sports body in the world is the presidency a paid job. The administration doesn't become professional just by appointing a professional. It's the mode of the management that has to be professional. Just by paying a man you don't make him a professional. In fact, if it was a paid job, a man like me could never have got it.

But why should specialist jobs be honorary? For example, why should national selectors be elected?

That's a different issue. There is debate on this issue and perhaps rightfully so. Many things are being done, many things are in the pipeline. Things have happened at lower levels already. Talent Resource Development Officers (TRDOs) have been appointed to scout talent. A TRDO can't recommend boys from his state. And he can't just say that this boy is good or that boy is good. He has to fill up a chart and explain why. These records are placed before the junior selection committee. You will ask, why only the junior selection committee, why not the national selection committee? And why five national selectors, why not three? My problem is not to get the board to agree. The problem is finding three men of stature who are willing to take it up professionally. Sunil Gavaskar will not come; he has his media assignments. Ravi Shastri will not come.

But there are others too. Dilip Vengsarkar would be happy to lead a non-zonal committee.

Dilip Vengsarkar is already doing a job for the juniors as a paid employee [chairman of TRDO] with a salary of Rs 15 lakh a year. You will agree that is good money. He is accountable and responsible for developing junior cricket.

What drives you? This is an honorary job and you are a busy man running a business full-time. What makes you spare so much time and effort for cricket?

I could just say it's the love for the game, which is undoubtedly there. But there's more. A senior football administrator, a good friend of mine, once asked me: what's the point in doing all this when people are forever questioning our motives when we work with so much sincerity and honesty. I asked him: are we really that honest? Honesty is not only about not being corrupt. We may not want to admit it, but in a corner of our hearts, isn't there a desire for recognition, for having more contacts and friends, being on television and in newspapers? The Tatas and Birlas and Ambanis have made much more money, but it's nice to be known in the world. Yes, you get criticised often, sometimes rightly, often wrongly. But there are plenty of people who recognise and appreciate what you have done and that's quite satisfying. God has given me enough for a couple of generations and I don't need material rewards from cricket.

But yet, fingers were pointed at you during the match-fixing scandal.

It hurt. People jumped to all kinds to conclusions without any evidence. Nothing was found, and I was never harassed by the CBI really. But still everybody started saying that the administrators must have known about match-fixing. We never had a clue. I asked the press: did you know, you travel with the team all the time, did you know who was involved?

Would it be right to say that you have not forgiven your colleagues at the ICC for not standing up for you then?

I don't know what to say. I think everybody, including me, was dumbfounded. I couldn't figure out what was happening, what was the magnitude of it. A lot of things became clear later. But at that time there was so much speculation. Some journalists wrote whatever they wanted to, but what came of it? Nothing. It took cricket back by 20 years. The money dried up. The sponsors went over to Kaun Banega Crorepati.

Surely, you are not suggesting that match-fixing didn't exist. Or that it isn't an evil?

Of course not. What I am saying is that a lot of irresponsible statements were made at that time and a lot of irresponsible and motivated journalists wrote things without a shred of evidence. They certainly didn't help cricket. Match-fixing should have been investigated thoroughly by the investigating agencies, but the trial by the media was wrong.

This interview first appeared in the June 2003 edition of Wisden Asia Cricket

Sambit Bal is editor-in-chief of ESPNcricinfo. @sambitbal