The amazing Sobers' amazing series

In England in 1966, he glowed with the bat and toiled with the ball in a comprehensive win, but were his efforts better than Imran's against India in 1982-83?

Stuart Wark

Oct 2, 2013, 12:16 PM

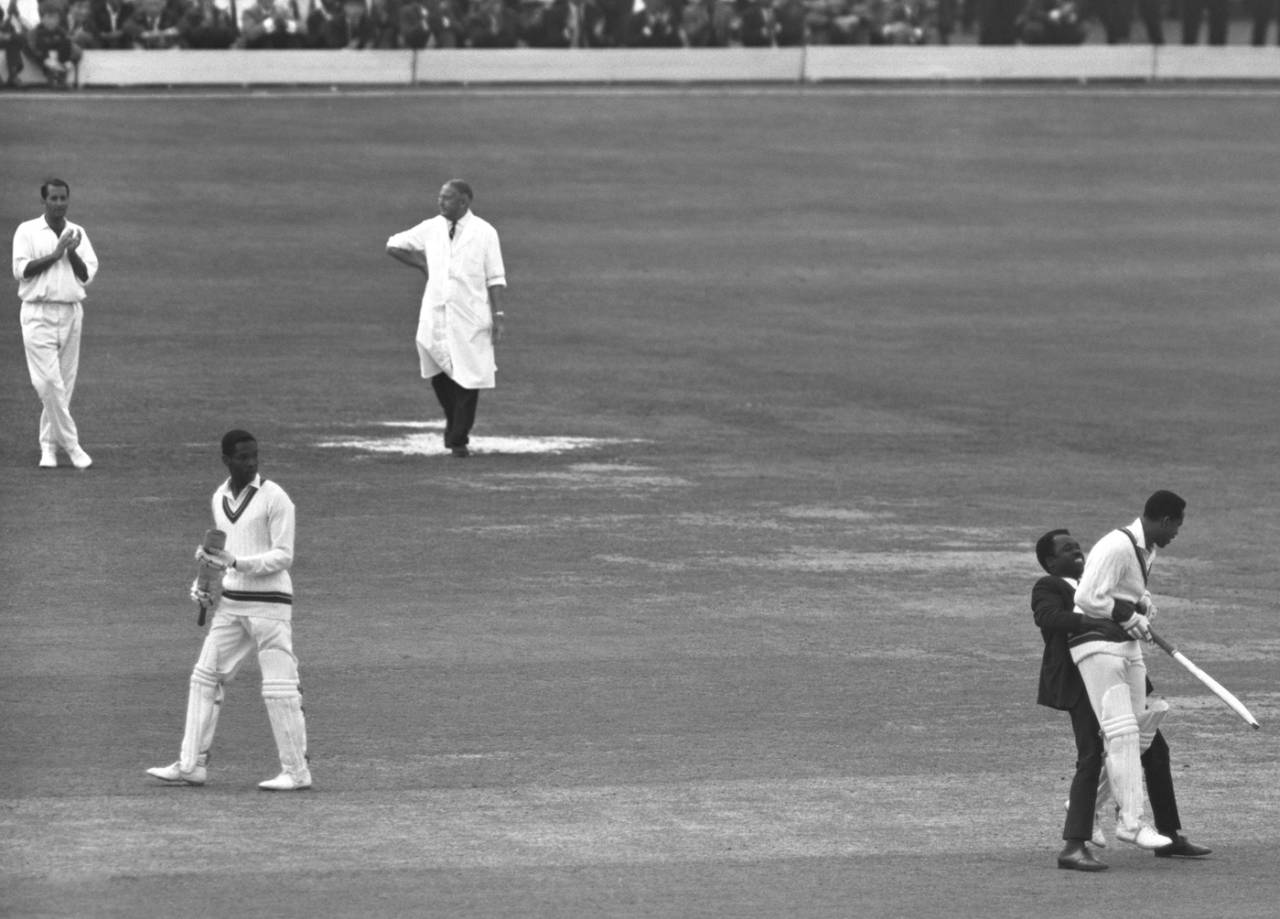

A spectator can't contain his admiration for Sobers during his unbeaten 163 at Lord's • PA Photos

In my last article I argued that Imran Khan's effort against India in 1982-83 was the greatest all-round performance in a single series. In response, a number of articulate readers put forward their view that Garry Sobers' 1966 achievements against England exceeded those of Imran. Without wanting to rehash a straight comparison between the two, I did think it worth examining Sobers' performance in that series and to then ponder why still I rate Imran's achievements as being better.

Cricket in the mid-1960s was starting to go through a period of significant change; the traditional powerhouse nations of Australia and England were both in a state of transition and, possibly for the first time in history, neither could claim to possess the best team in the world. West Indies had been steadily improving from the narrow loss in the tied Test in the 1960-61 series against Australia and were now seen as the true world power. They had beaten England 3-1 in 1963 and Australia 2-1 at home in 1964-65 - their first win over the side.

West Indies had a very strong batting line-up, with Conrad Hunte, Basil Butcher, Rohan Kanhai and Seymour Nurse all averaging around 45 in Test cricket. They were well supported by a fast bowling line-up that included Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith, and the world-class offspin of Lance Gibbs. But to top it all, they had Sobers. He had played 52 Tests by 1966, and was recognised as probably the best batsman in the world, with a batting average of 56.32. However, his all-round ability to also bowl medium pace and spin, as well as his amazing fielding skills, added further jewels to his crown as the leading cricketer of the era.

Sobers was named captain of the 1966 West Indian touring party for England. It is interesting to reflect now that West Indies played eight first-class games prior the first Test. In the 2013 Ashes, Australia played two. Whether more first-class games would have helped Australia this year is debatable, but it is clear that West Indies in 1966 were more than ready by the time the first Test commenced in Manchester. They proceeded to smash the home team by an innings and 40 runs. Hunte made 135 and Sobers a masterful 161. In reply, England were bowled out for 167 and 277. The main destroyer was Gibbs, who took ten wickets in the match. Sobers failed to take a wicket in the first innings, but bowled a marathon 42 overs in the second to take 3 for 87. In one of the early examples of such awards, Batsman of the Match was awarded to Sobers and Bowler of the Match to Gibbs.

The second Test, at Lord's, was drawn but either team could have won it. Mike Smith was replaced by Colin Cowdrey as the England captain. This time West Indies made only 269 and England took a lead of 86. Hall took four wickets and Sobers 1 for 89. West Indies were deep in trouble in their second innings when Sobers came to the crease. He then produced a magnificent unbeaten 163 in partnership with his cousin David Holford, who made a similarly undefeated 105. The pair took the score from 95 for 5 through to the declaration at 369. England required 284 to win, and in spite of a wonderful century from the hard-hitting Colin "Ollie" Milburn, the game finished tamely. Sobers was again Batsman of the Match, while Ken Higgs got the bowling award for his eight wickets.

For the first few days, the third Test, at Trent Bridge, followed a similar script to the second. England took a lead of 90 based around Tom Graveney's 109 and Cowdrey's 96. Sobers (who made 3 in the first innings) and Hall opened the bowling and took four wickets each. Sobers' effort in bowling 49 overs was a sign of his excellent fitness. In their second innings, Basil Butcher rescued West Indies from a position of two wickets down and still 25 behind, with his finest Test innings, 209 not out. Chasing 393 for an unlikely win, England were bowled out for 253. Griffith took 4 for 34. Sobers took 1 for 71, but bowled 31 very economical overs in the process. Somewhat surprisingly, double-centurion Butcher was overlooked for the Batsman-of-the-Match award, which went to Nurse for his first-innings 93. Again slightly strangely, the bowling award was given to Higgs.

I always find it fascinating to read comments that Sobers was not the greatest allrounder of all time because his bowling isn't perceived as being good enough. This argument is often backed up by the claim that Sobers was never picked for West Indies as a bowler only. Even the briefest research will immediately kill this premise dead. In fact, Sobers made his debut for West Indies as a left-arm orthodox and batting at No. 9. Admittedly his batting genius was soon uncovered and it quickly exceeded his bowling exploits, but it is worth remembering that Sobers did initially play for West Indies purely as a bowler. What is more remarkable is that he could bowl at a Test standard in three different styles: left-arm orthodox, left-arm legspin and left-arm fast medium.

I feel that at times this amazing flexibility actually counted against him. If the pitch was green, selectors could stack the team with more quicks and use Sobers in a holding pattern with his slow left-armers. If the track was dusty the team would have more spin options and Sobers could be used to take the shine off the new ball. This willingness to bowl in a style that suited the team while perhaps less conducive to getting wickets, speaks well of the man, but it also has resulted in a bowling average that is higher than would be expected, given his skills with the ball. The third Test was an example of this, with Sobers bowling an extraordinary number of overs to hold up one end while Hall and Griffith attacked at the other.

The fourth Test was another one-sided affair that West Indies won by an innings and 55 runs. Batting first, West Indies declared at 500 for 9. Nurse and Sobers both made centuries, their partnership taking the score from 154 for 4 to 419 for 5. Sobers followed his top-scoring 174 with 5 for 41. However, it could be argued that this time he was the beneficiary of the efforts of the other bowlers. Hall and Griffith bowled with considerable pace and venom and quickly reduced England to 49 for 4 and forced Milburn to retire hurt before Sobers removed the final five. In the follow-on, Gibbs took six wickets, but Sobers was named both the batsman and bowler of the Test.

In a precursor to events in 1988, the dominance of the West Indian team in England saw yet another change to the captaincy for the final Test. Colin Cowdrey was now replaced by Brian Close, who had debuted for England 15 years earlier in 1949, hadn't played a Test for three years, and would go on to play his final Test match another ten years later, in 1976*. However, unlike in 1988, having a third captain in the series paid off for England. Sobers won the toss for the fifth straight time, chose to bat and scored 81 out of a total of 268. Graveney and John Murray made hundreds in England's reply of 527, during which Sobers bowled an astonishing 54 overs in taking 3 for 104. But he finished his series with a first-ball duck, caught by Close off John Snow. While England had regained some pride by winning this final match by an innings, ultimately West Indies had easily won the series 3-1.

Sobers' efforts in 1966 were amazing. The statistics alone bear this out - 722 runs at an average of 103.14, 20 wickets at 27.45 and ten catches.

So why do I still think Imran's achievements were greater? On paper, you could easily make a highly compelling argument for Sobers, and I fully respect the opinion of anyone who does think that way. However, a few of my reasons for taking an opposing view relates to the relative strengths of the teams for whom they played.

West Indies were the No. 1 team in the world in 1966, whereas Pakistan in 1982 were still trying to establish their credibility on the world stage. Sobers' bowling in the series was strongly supported by the opening attack of Hall and Griffith, and the spin of Gibbs. A quarter of Sobers' 20 series wickets came in one innings, when he polished off the final five wickets after Hall and Griffith has decimated the top order. For much of the series he fulfilled a "holding" role, in which he bowled a massive number of overs very economically but without taking bags of wickets. Similarly, Sobers was not the only West Indian batsman to score big runs throughout the series, although it must be acknowledged he was clearly the most consistent. He didn't have to continually operate on his own in the way that Imran carried the bowling load for Pakistan while also contributing with the bat.

However, on reflection I have been forced to wonder why I rate Imran's performances higher. There is clearly a strong emotional aspect to the decision. I have tried to analyse it, and can only come up with the argument that the fast-bowling allrounders somehow capture the imagination better than batting or spin-bowling allrounders. Aubrey Faulkner is hardly ever mentioned in the list of great allrounders, but a career Test batting average of 41 and bowling of around 26 compares more than favourably to the legendary figures of Keith Miller (37 and 23), Imran (38 and 23) or Botham (34 and 28). I think that perhaps the mystique that surrounds fast bowlers may influence us to consider their achievements as being somehow greater than those of their less pacy equivalents.

None of these observations should be seen as criticisms in any way of Sobers or his amazing performance in 1966. I rate Sobers as the greatest cricketer the world has ever seen. If I ever play the popular internet-forum game, "Select the greatest World XI", I start with Bradman at No. 3 and Sobers at No. 6 and then work the rest of the side around them. However, it does not mean that the greatest allrounder in history must necessarily have produced the best series performance. Sometimes statistics are not proof in themselves, and the great joy of cricket is that it allows viewers to make subjective and emotional decisions based purely on love rather than hard data.

* Brian Close's Test career covered a period of 26 years 356 days. Chronologically this is the second-longest career in terms of time, with only Wilfred Rhodes' 30 years 315 days between debut and retirement exceeding it. Sadly, Close only played a total of 22 Tests over those near three decades of play and his immense talent was perhaps never entirely realised at the international level.

Stuart Wark works at the University of New England as a research fellow