Big wedge, thin end

“There can be no normal sport in an abnormal society.” Thus was the stance of the South African Cricket Board during Apartheid

Rob Steen

25-Feb-2013

Getty Images

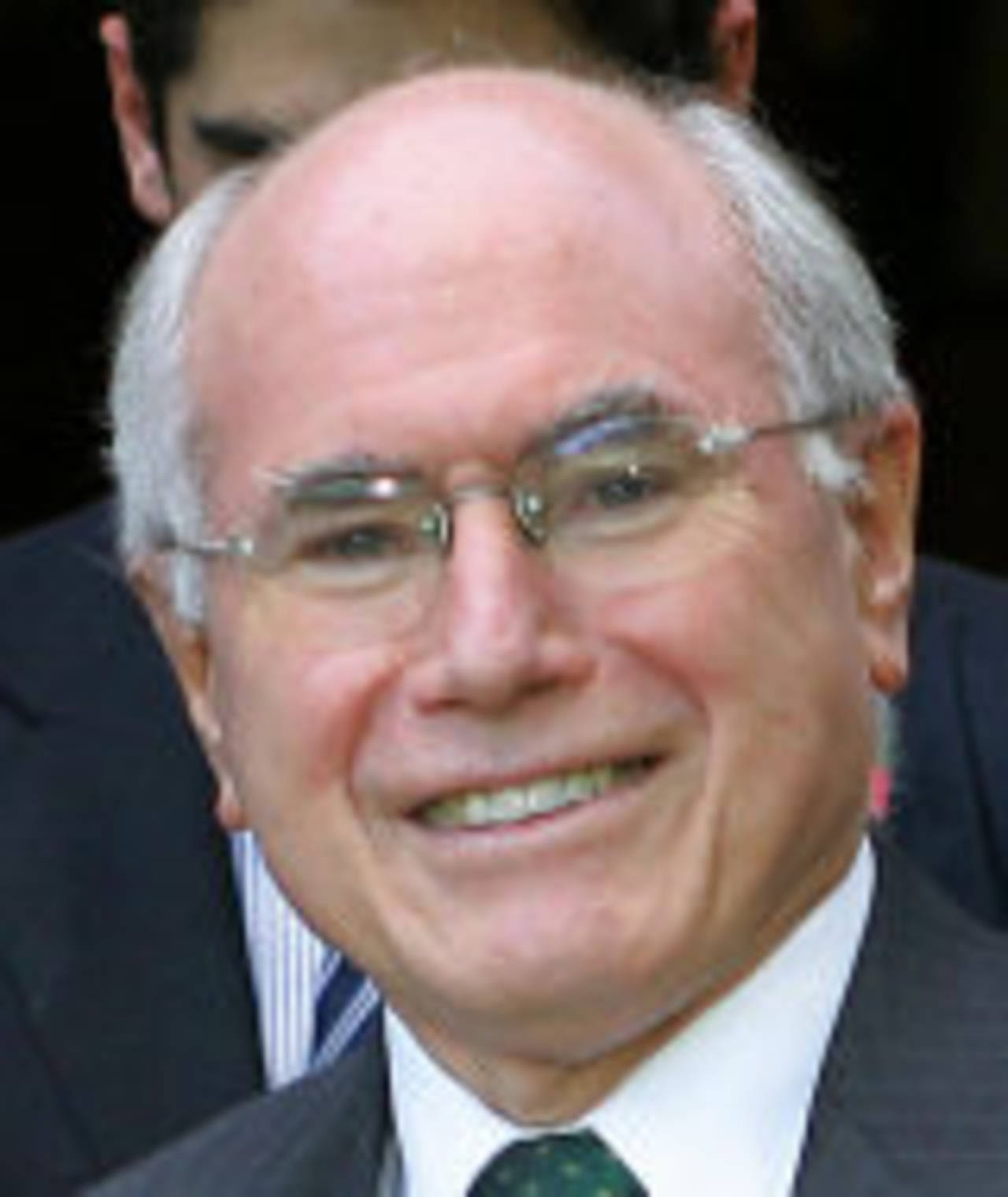

As for boycotts, Kevan Gosper, the International Olympic Committee vice-president and an Australian, said the following prior to the 2003 ICC World Cup: "In suggesting he would like to see an agreement between all the countries that we not play World Cup cricket in Zimbabwe, (Australia) Prime Minister John Howard is giving new life to the dreaded sporting boycott. To do this on the basis that the issue is one of principle is misguided. It can only damage our sporting reputation. Sport is all about providing opportunities for all, particularly for the younger generations. Boycotts have no part in this generation building.” By way of underlining the IOC’s tolerance, Tomas Amos Ganda Sithole, President of the Zimbabwe Olympic Committee, had just been named as the new director of the IOC’s International Cooperation and Development Department.

Gosper, who supported an Australian boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics, should have known better than to perform such an obvious u-turn. But then what else can one expect of the IOC, which once led the way by banishing South Africa but whose showpiece became so prone to boycotts in the 1970s and 1980s that it now puts humanity a distant second behind money? Not that its counterparts in soccer or rugby union have any more to shout about.

Yet political demonstrations by sportspeople, from Tommie Smith and John Carlos’s “Black Power” salute at the 1968 Olympics to the recent denouncements of Beijing’s part in the horrors of Darfur, can be a powerful unifier and a persuasive tool. Such is white South Africa’s passion for ballgames, the sporting boycott, whose muscle and impetus sprang from the D’Oliveira Affair, was a significant factor in the slow death of Apartheid - as Nelson Mandela acknowledged when he expressed his gratitude to D’Oliveira. And cricket severed relations with the Republic a good deal sooner than rugby. Yet only a minority of ICC full members, all supposedly “civilised” sorts, now see playing games with Zimbabwe as beyond the pale. That England and Australia should be the most voluble might well convince cynics that this is merely a legacy of the spotlight on seizures of white farms that so dominated newspaper coverage a couple of years ago, though this aspect seldom features now.

John Howard achieved one of the few indisputably worthwhile feats of his premiership last year when he informed Cricket Australia that touring Zimbabwe was simply not on, though some believed the decision owed more to fear of violent national elections. "The Mugabe regime is behaving like the Gestapo towards its political opponents,” declared Howard. “The living standards in the country are probably the lowest of any in the world, you have an absolutely unbelievable rate of inflation. I have no doubt that if this tour goes ahead it will be an enormous boost to this grubby dictator."

The trouble with Gordon Brown’s government is the mixed messages it is sending. In January, David Milliband, the foreign secretary, said: "I think that bilateral cricket tours at the moment don't send the right message about our concern. This is something that needs to be discussed with the ECB and others.” The key word used by Milliband, interpreted the subsequent report on this very website, “is bilateral”. Roughly translated, this means that although the Labour government may effectively prohibit England from playing series against Zimbabwe, the latter would be permitted to participate in a multi-nation competition such as … well, the ICC World Twenty20. Which is due, after all, to be staged in Blighty after Zimbabwe’s scheduled tour in 2009. Any suggestion that Zimbabwe would be unwelcome for that event would almost certainly lead to those uncommonly profitable hosting rights being transferred to some other lucky country more inclined towards moral flexibility. This is, of course, utter rot of the rottenest kind. Not so much a case of having your cake and eating it as buying the entire bakery and scoffing every last crumb of the stock.

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

|

To aggravate matters, Lord Malloch-Brown, the Foreign Office minister, told the House of Lords earlier this month that the government would not bar Zimbabwe from playing in England in 2009. Not unexpectedly, Kate Hoey was almost beside herself: "It does not seem to reflect the views of Downing Street earlier this year. It would be a travesty if we gave visas to any Zimbabwean cricket team to tour and I want to see the prime minister clarify the situation." A clarification of sorts came a few hours later, when a source close to the prime minister reaffirmed the government's stance. "We will not leave the ECB in the lurch and expect them to take the responsibility," he was quoted as saying by The Times. "We will talk to them over the next few weeks over how this is done, but we are against it and the world will know we are against it."

Now that national boards are fined for failing to fulfil their duties to the Future Tours Programme, waiting for governments to intercede has become the no-option policy of choice, a shrewd way of passing a morally-bankrupt buck. International cricket needs to reclaim the principles that eventually, after extensive and unconscionable English and Australian feet-dragging, led to South Africa being barred from official cricket in 1970.

Better yet, it needs to follow the brave lead of Stuart MacGill, who refused to tour Zimbabwe in 2004 because his conscience forbade it (others have made similar noises but without quite the same conviction). It was a conversation with Andy Flower, he revealed in a TV interview two years later, that made his mind up: "Andy said: ‘I really applaud your thinking, but it's not going to change anything. The only reason that you should pull out of this, if you are thinking in that way, is if you just don't feel comfortable going there.’ That's really how that cemented my opinion.”

Of course he was petrified that it might have cost him his Test career. “I'd have been devastated, but I think it was still the right thing to do and I made my decision based on that.”

But is touring a nation any more morally bankrupt than hosting its purported representatives, even playing them on neutral turf? Yes, but only for those whose philosophy begins and ends with that most apathetic of mantras - see no evil, hear no evil. By realising this and acting on it, the ICC will also have the not inconsiderable satisfaction of embarrassing two sporting governing bodies that beat it for naked greed, namely FIFA and the IOC. Now THAT’S what I call the spirit of cricket.

Rob Steen is a sportswriter and senior lecturer in sports journalism at the University of Brighton