Hutton, Compton and the resumption of county cricket in 1946

We look back to the summer of 1946 and the return of the County Championship after a seven-year absence

Paul Edwards

Apr 23, 2020, 9:38 AM

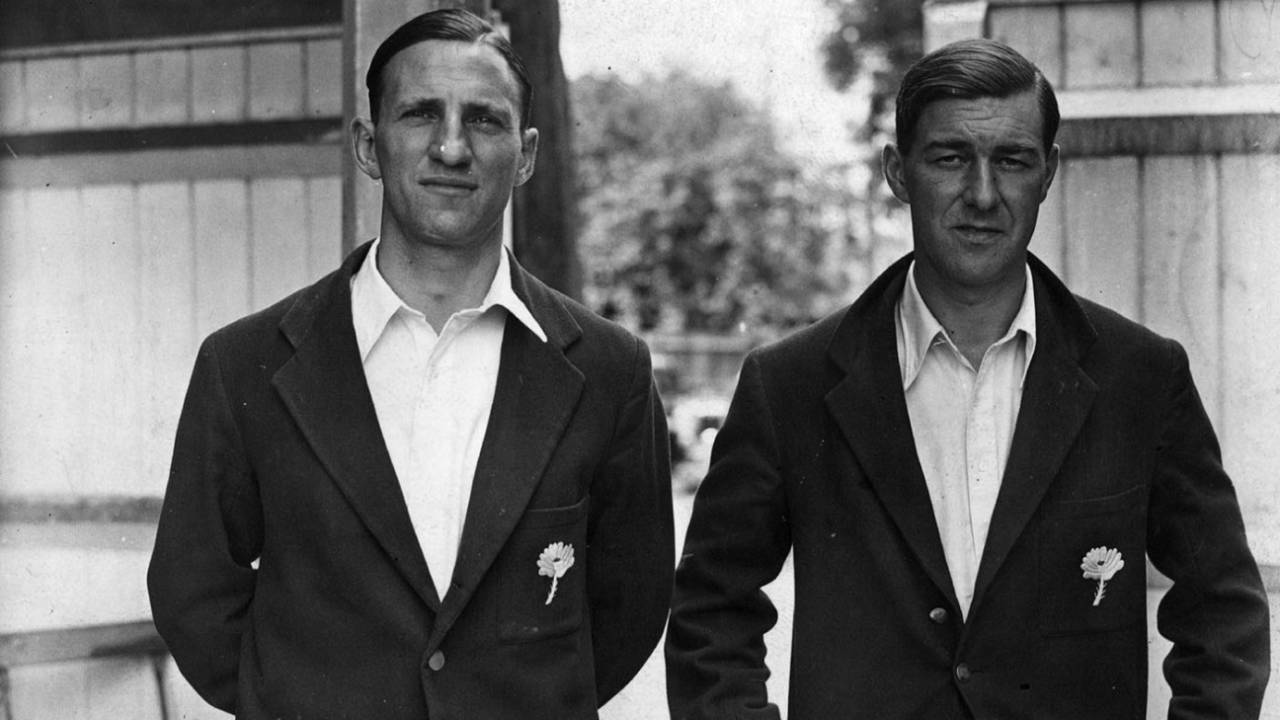

Len Hutton and Norman Yardley pictured in their Yorkshire blazers in 1946 • Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In our series Match From the Day, Paul Edwards revisits classic county games.

May 10, 1946

Middlesex 275 for 6 dec (Robertson 88, Compton 74, Brown 65) and 142 for 2 dec (WJ Edrich 51*) beat Leicestershire 147 (Berry 76, Sims 5-53) and 205 (Watson 74, Gray 3-46, Sims 3-89) by 65 runs

Scorecard

Scorecard

May 13, 1946

Yorkshire 195 (Hutton 90, E Davies 5-37, Clay 3-41) and 84 for 5 (E Davies 3-28) beat Glamorgan 116 (E Davies 54, Robinson 7-22) and 162 (Booth 4-40, Robinson 4-77) by five wickets

Scorecard

Scorecard

Just before lunch on September 1, 1939 Yorkshire's cricketers completed a nine-wicket victory over Sussex at Hove and Leicestershire's players agreed with their Derbyshire counterparts that no play would be possible on the final day of the game at Aylestone Road. Earlier that morning German troops had invaded Poland.

Yorkshire's 12th man was Herbert Sutcliffe and John Marshall reports that just before he began his drive home he remarked to Sir Home Seton Charles Montagu Gordon, 12th Baronet Gordon of Embo, Sutherland, that it would be three years before they watched another Championship match. "More likely five," replied Gordon, who was also a journalist and a devoted Sussex supporter. As things turned out, it would be nearly seven years, 2440 days indeed, before Middlesex chose to bat against Leicestershire at Lord's on May 8th 1946 and Denis Compton made 74 on the first afternoon. Compton's batting in those post-war summers was to offer proof that all bad things must come to an end.

But not all matters were as clear or joyous as that. The outbreak of war in 1939 had caused the cancellation of the Scarborough Festival and also three Championship matches, the latter fact being noted with characteristic restraint by Wisden: "Middlesex v Kent, Gloucestershire v Nottinghamshire and Lancashire v Leicestershire were not played because of the international situation at the beginning of September."

Then, to general delight, first-class cricket had resumed in 1945, over two months before the war in the far east had ended. But only 11 games had been possible, five at Lord's and three at Scarborough. Six of the matches had involved the famous Australian Services side and the only county match, Yorkshire v Lancashire at Bradford, had been played as a benefit for the dependants of Hedley Verity.

Ah yes, Verity. If Yorkshire supporters deluded themselves that retaining the title in 1946 signified that nothing had changed since they had won it in 1939, they had only to recall the supremely skilful, slow-medium left-arm spinner who had died of his wounds in Caserta, Italy in 1943. And however hard all county officials strove to put out 11 players for each match in 1946, there were poignant gaps which willing substitutes could not fill. Yorkshire supporters watching their side's opening Championship match against Glamorgan at Cardiff Arms Park may have noted Verity's absence but Glamorgan were without Maurice Turnbull, who had died near Montchamp in France less than two years earlier.

Both Verity and Turnbull would have been in their forties when Championship cricket resumed in 1946 but no one doubts they would have played in the game. For one thing their skill was not in doubt; for another, every county needed all the players they could find in cricket's make-do-and-mend years. There were six matches in that first round of Championship games and the 12 county sides contained 23 men in their forties and only two under 25. As far as possible the government had encouraged cricket during the war but no club had been able to develop its young talent as it had done in peacetime. The average age of the Glamorgan team that lost to Yorkshire by five wickets was 38 but Brian Sellers' side was also far past its prime, a fact noted with his usual elegance by JM Kilburn.

"The old Yorkshire took one curtain call. They won the championship of 1946. They won it essentially as trustees of tradition and reputation because most of the regular players were within a season or two of final departure and only Hutton, Yardley, Gibb and Robinson had careers of any consequence ahead of them."

Hedley Verity was one of those cricketers who did not return from the war•Hulton Archive/Getty Images

No one was untouched by the war. Len Hutton made 90 in Yorkshire's first innings at Cardiff but did so with his left arm permanently shortened, the consequence of a series of operations following a fracture suffered during his service in the Army Physical Training Corps. Bill Bowes returned to the side and even played in the first of that summer's three Tests against India but he had spent three years in Italian and German prison camps. Kilburn duly noted that he "came back to cricket under clear medical warning that the fast bowling demands of younger days should never be imposed on his physical capacity".

Verity's replacement - a notion considered heretical in Rawdon and Horsforth Hall - was Arthur Booth, who was 43 and had been considered Wilfred Rhodes' successor in the late 1920s until Rhodes' longevity and Verity's arrival ended that debate. Booth had played just five first-class matches for Yorkshire, and none in the Championship since 1931, prior to being summoned from the league cricket to play a vital role in his county's attempt to win their eighth title in ten seasons. He responded by taking 111 wickets at 11.61 each and at an economy rate of 1.4 runs an over.

In his particular way Booth epitomised the tight Yorkshireman and was nearly selected for MCC's ill-starred tour to Australia in 1946-47. Instead he stayed at home during one of the coldest winters ever recorded and caught rheumatic fever. He played just four more matches for Yorkshire, who were not to win another outright Championship until 1959.

But that Arms Park match is worth recalling for two other fine individual performances. Emrys Davies, Glamorgan's opener and slow left-armer, made 54 and 30 and took eight wickets, twice dismissing Hutton if you please, while 11 of the home side's batsmen fell to the offspin of Ellis Robinson, who was to take 129 Championship wickets on that season's wet pitches.

Yes, the weather in 1946 was dreadful. Hubert Preston, the 78-year-old editor of Wisden, debated with himself whether it was worse than that of 1888 and eventually decided it was. But Preston's overall judgement that "although handicapped by execrable weather…the resumption of first-class cricket showed in every way how ready players and public were to welcome their favourite pastime" was reflected in good attendances at most games and the gates being shut at a few venues.

Bill Edrich and Denis Compton walk out to bat for Middlesex•PA Images Archive/Getty Images

In 1942 cricket had offered a relief from war; in 1946 it became a confirmation of peace. Few people, except the very wealthy and those still serving in the forces, could dress well and many grounds showed the effects of their wartime uses. The Oval had been requisitioned by the War Ministry and was employed initially for barrage balloons, then as an assault course and, finally, for cages to accommodate prisoners-of-war. This last enterprise involved driving 2,000 posts into the turf. The prisoners never arrived but the cricketers expected to play in 1946, so groundsman Bert Lock organised the transportation of tens of thousands of turves from the Gravesend Marshes. Once they were laid, Lock tended and rolled the surface until the old place resembled a cricket ground once more.

It was easier to restore grounds than it was to improve the condition of the people. Britain had all but bankrupted herself to defeat fascism, food was still severely rationed and many inner cities had been flattened by the Luftwaffe. "I was always hungry" said Bill Edrich, who had led an RAF squadron and won the Distinguished Flying Cross in the war. "It was noticeable, too, how shabby everyone looked. I had to renew a lot of cricket gear, so the coupon situation soon grew difficult for me also."

The easy and rather naive response to all this was that Britain hardly looked like a victorious country. Then one remembered that in 1945 the country had held a democratic election, that one could read about Compton's batting in a free press and that one's government, of whatever stripe, did not commit genocide. It might also be worth recording that two years after that first round of matches the NHS was established.

And so in May 1946, removed in temperament if not always in miles from the chambers of political debate, people gathered to watch county cricket. At Taunton, Tom Pearce made an unbeaten 166 as Essex beat Somerset by two wickets; at Trent Bridge, Walter Keeton's 160 steered Nottinghamshire home against Kent; at Southampton, George Heath's nine wickets helped Hampshire get the better of Worcestershire; at the Wagon Works Ground in Gloucester, Walter Hammond made a century in the first innings against Lancashire but was absent with a strained back in the second as the visitors won by 135 runs; and at Lord's, Compton made 147 not out in the first innings against Northamptonshire before being run out for 54 in the second. The game was drawn but Denis had started as he was to continue.

Did it matter? No, not much. Did it matter? Yes, terribly. And one man who understood why that question has two answers was beginning his cricket broadcasting career in May 1946. The BBC had noticed the arrival of the Indian tourists and a 32-year-old Literary Programmes Producer with the Overseas Service had volunteered to cover their matches at Worcester and Oxford. At The Parks he had seen the graceful New Zealand left-hander Martin Donnelly make 61 and 116 not out. Having served as a policeman during the Blitz in Southampton, John Arlott probably could not believe his luck.

For more Match From the Day stories, click here.

Paul Edwards is a freelance cricket writer. He has written for the Times, ESPNcricinfo, Wisden, Southport Visiter and other publications