The man behind the ground

GD Martineau recalls the life of the man who gave his name to the most famous cricket ground in the world

25-Nov-2005

|

|

|

The story of Lord's and the MCC has been told many times, and, since it is a good story, will be told many times again. Let us dwell for a while on Thomas Lord himself. What do we know of the character of this Yorkshireman, immortalised through the association of his name with the Headquarters of Cricket ?

Two artists have given us some idea of his appearance. One, George Shepherd, drew him at the age of about 34, apparently in the act of holding a catch - bent double, as though to make assurance doubly sure. Another, fainter sketch, but without a name attached, shows a figure standing upright, preparing to bowl underarm; both drawings portray a wide hat, short jacket, and knee-breeches. Next we have George Morland's oil painting, made 20 years later, showing a good-looking, clean-shaven man, with large forehead, receding hair, shrewd eyes, and tight lips. There is also the silhouette of Lord and his wife, but it adds little to these impressions. If we consider them in conjunction with his family background and personal career, we obtain some idea of the man.

To begin with, the Lords were "Yorkshire through and through." In the 17th century, we find Thomas Lord of Brampton and George Lord of Vickersley, landowners and Roman Catholics, as was George Lord's grandson. William, who owned a farm at Thirsk in 1745. That year profoundly affected the fancily fortunes, for William Lord, by raising a troop of horse for Bonnie Prince Charlie, forfeited his possessions. Later, he came back to work as a farm-hand on what had once been his own property, and there, on November 23, 1755, Thomas Lord was born.

The next move was to Diss, in Norfolk, where the boy was educated and learnt his cricket, before going to London at the age of about 24. How exactly he earned his living at first is not certain. Roman Catholics were suspect, trouble was brewing, soon to boil over in the devastating Gordon Riots, and there may be a connection between these circumstances and the fact that Thomas Lord was the first member of the family to become a Protestant.

He is next heard of as a bowler and general attendant in the service of the White Conduit Club at Islington, and particularly of the 9th Earl of Winchilsea. He was now an active cricketer, standing 5 feet 9 inches and weighing 12 stone, a smart fieldsman at point, and a good bowler. His bowling is described variously as slow and extremely rapid, which may be accounted for by different phases in the development of his attack. At all events, he bowled to the Earl and his friends, who also liked him personally, so that when, in 1786, Lord Winchilsea and Charles Lennox were becoming dissatisfied with White Conduit Fields, it was natural for them to turn to the genial and capable Yorkshireman and offer to guarantee him against loss if he would open a new ground.

With this powerful backing, he approached the agent of the Portman family and arranged to rent a strip of land in the then almost completely rural district where Dorset Square now stands.

|

|

|

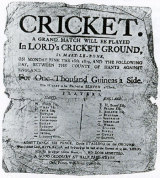

What purports to be Lord's first ground, Dorset Fields, is the subject of a picture in Sir Jeremiah Colman's collection at Lord's, though the considerable hill rising in the left background leaves one in some doubt. The opening of that ground in May, 1787, and the formation of the MCC, meant that Hambledon had had its glorious day, and Thomas Lord lost no time in enclosing it with a fence and charging an entrance-fee of sixpence.

There the Club flourished for more than 20 years, while London grew larger. In 1793 Thomas Lord married Mrs. Amelia Smith (nee Angell), a member of a well-known North London family. She was the widow of a Proctor in the firm of Burgoyne, one of whom, Thomas Burgoyne, was Treasurer of the M.C.C. Their only son, also Thomas Lord, was born in the following year.

By 1810, when pickpockets and cut-throat gangs had penetrated into the once quiet neighbourhood of Dorset Fields, the lease had run out. Lord, for some time the lessee of a local inn which the cricketers probably used as a changing-room, had already foreseen this, and, refusing a demand for increased rent, concluded an agreement with the Eyre family for a new ground, on the St. John's Wood estate.

When this move proved unsatisfactory, and was finally invalidated by a Parliamentary decree that the Regent's Canal should be cut through the centre, it was the Eyres who came to the rescue and offered the present ground, opened in time for the season of 1814.

During this period, when the fate of Lord's and the MCC hung in the balance, that steady Yorkshire determination came out. The man who, having lifted and transferred the turf of Dorset Fields to that second ground, could repeat the process in the face of failure, and have it carried to a third, was a character to be reckoned with ; and it is interesting to notice that Morland's portrait dates from about the time of the move from Dorset Square.

The hard early struggles which were the legacy of his father's Jacobitism left their mark on him, and produced a canny man of business. Pycroft believed that Lord was Scotsman, and he acquired at tines a reputation for being close-fisted, as for example when he refused to pay the 20 guineas claimed by Edward Budd for hitting a ball out or Dorset Square. He always kept a vigilant eye on the financial aspect, knew the value of advertisement, and would run up his flag as a signal to the public that a " grand match' was on, bringing them in thousands to pay their sixpences.

The cautious tendency made him an extreme conservative in matters of cricket, so that he viewed the round-arm revolution with profound distrust. He is described thus at one of the experimental matches of 1827: "The old captain of stumps, Lord, a good fellow, and with a heart panting, old as it is, for cricket, waxed desperately hot on the occasion, and neither civil nor adverse treatment could recover his good humour."

|

|

|

Two years earlier, after an interview of historic brevity, he had ceased to be proprietor of the ground that bore his name. "It's said you are going to sell us!" challenged William Ward, and Lord, who had been planning to sell all but a small inner space for building, admitted that he would dispose of the ground if he could get his price.

"What is your price?" demanded Ward, and, on being told £5,000 (which was considered a very steep figure), brought out his cheque-book, exclaiming : "Give me pen and ink!"

Lord's, then, for the time being, became Ward's.

Old Tom and Amelia Lord (he was now close on 70) continued for a while to live in their house in St. John's Wood, overlooking the south-eastern corner of the ground, and then, the following year, came the news that his old employer, the Earl of Winchilsea, was dying. Deeply distressed, he hastened to his bedside, and those who believed him hard-fisted would have gained a fairer idea of his character from his genuine grief on this occasion, and from the fact that he sought no advantage for himself but spent some time urging the Earl not to disinherit one of his relatives. When this question had been disposed of, and Lord Winchilsea demanded: "Now, Lord, tell me - what can I do for you ?" He replied: "Nothing ... nothing!" Finally, when pressed, he asked only to be allowed as a personal memento a drinking-glass which had been made specially for the Earl after he had been wounded in the mouth on active service.

In 1828 Amelia Lord died, at the age of 74, and was buried in St. John's Wood Churchyard, and, two years later, Lord, having decided to leave London for the country, took a farm at West Meon, in Hampshire. It seems a strange thing for a man to have done so late in life ; but he was, after all, a farmer's son, born on a farm, and perhaps, remembering his father's dispossession, he felt that he was regaining for his son what had been lost in the adventure of "the '45."

He died on January 13, 1832, at the age of 76, and, though the most famous of cricket-grounds changed hands twice more before becoming the property of the MCC, the old name is jealously, indeed affectionately, preserved.

A few non-cricketers are still under the impression that it has a vague connection with the Upper House, and on that account regard cricket as a game under some sort of mysterious aristocratic control. No such mistake is likely to be made by Yorkshiremen, many of whom have an almost proprietary interest in those green acres in St. John's Wood ; for, in that oasis amid London's uproar, is immortalised the memory of one of Yorkshire's sturdiest sons.