With Umar Gul the Uncomplicated, what you saw was what you got

He had a clean kaput of an exit, the completeness of a career with no lingering sense of unfulfillment

Osman Samiuddin

20-Oct-2020

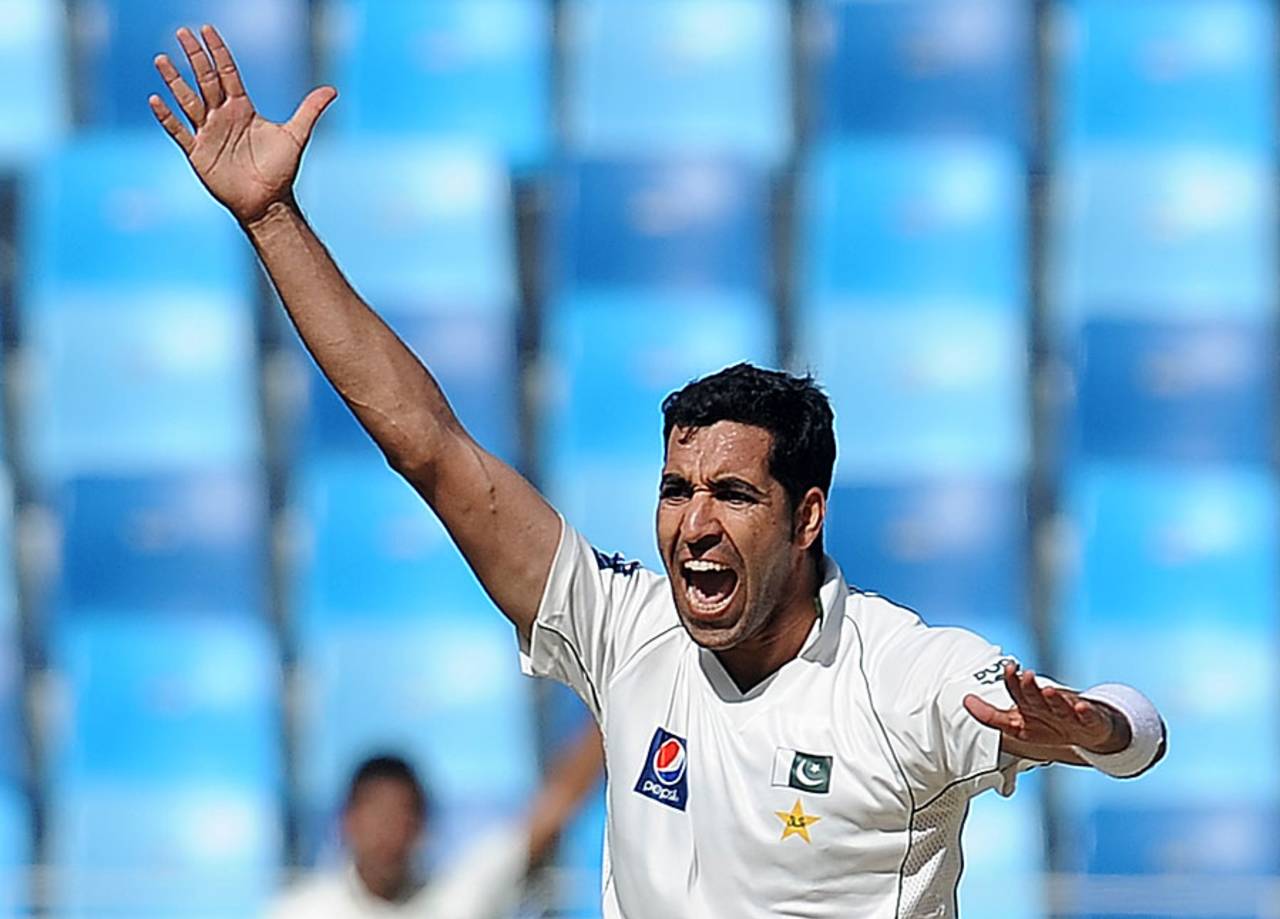

Umar Gul is Pakistan's highest Test wicket-taker in the post-Ws era by some distance • AFP

This was always one of Gul's most endearing traits: he is an uncomplicated figure. What you see is what you get is what he is, is what he said.

One of the more illuminating stories about Gul comes from that turbulent period in 2009, when players were forever angling to remove whoever was the captain. Gul, not hitherto part of any faction, was pushed by a senior player to complain about the captain in one team meeting in front of everyone. He did, but when the captain countered and asked why he was complaining, Gul said that he wasn't but that the senior player - present of course - had told him to and so he did. Rulers don't come this straight.

There was once an on-field squabble with Mohammad Amir over a dropped catch, and he recently - but gently - questioned the new domestic structure. But the PCB's very vast archives of player disciplinary breaches don't record an entry under 'Gul, Umar'. Somehow he even came out untarnished from the Tours from Hell, Down Under in 2009-10, after which the PCB punished anything with a pulse.

Putting all this front and centre may come across as a sideways dig at his bowling: his primary task, after all, wasn't to be a nice guy but to take wickets. It isn't intended to be. It's just that we know Pakistani fast bowling is a fraught beat. It comes with aches and traumas, joys and bedlam, buts and if-onlys; some days it is only marginally about the bowling, and the rest of the time, it isn't about the bowling at all. Almost none of it is good for the heart.

With Gul, his bowling came with zero baggage. The rules were simple. He could be exceptional, good, ordinary, poor or awful and that was it. Pack your bags, day's done, get on with your life, come back tomorrow. It may not always have been clear at the time, but with hindsight, that taste was sweet relief.

Underpinning it was the yorker which, if it didn't carry quite the spectacle of Lasith Malinga's, was arguably more effective. There was an unreal force around it, not least in how readily and accurately it was summoned.

Hindsight veers unevenly towards Gul with white ball in hand, with the canvas of the shortest format out in front at his mercy. Which is justified, but it's worth lingering for a bit on his red-ball career, which now falls some way between forgotten or misremembered.

No one can ever know what impact those stress fractures of the back had so early in his career. He'd taken 25 wickets in his first five Tests before the diagnosis, and he didn't play another Test for two years. In fact, his last act in that sequence - the five-for against India - was the definitive modern Pakistani spell against India, until Mohammad Asif came along. Pakistan bluster was all pace but here was the bluff, a kid who wasn't defined by pace, a kid with a natural length just back of good, who seamed the ball rather than swung it.

It wasn't so straightforward as that he wasn't the same bowler after it (and actually his Test numbers, right until the end of 2007, were solid). But other bowlers arrived, a new format emerged, and the occasions on which he looked that potent again changed, both in manner and frequency. Often, as against a competitive West Indies side, he looked as good as he has ever done: movement with the new ball, reverse with the old, big-name wickets with big-time deliveries, and match-shaping spells. Against stronger opposition, with comedy support, he was manful, as in England in 2006.

It says everything about Pakistan's pace resources in that era that he only played three Tests with Shoaib Akhtar and none after April 2004. And he only played 17 Tests with Asif and/or Amir, the pair for whom he seemed the perfect condiment.

Except it turns out he was better for their absence, even if Pakistan weren't. Partnering either or both, Gul took less than three wickets a Test, at 40; on his own, he took nearly four wickets per Test, averaged ten runs lower, with a strike rate 14 balls lower. The numbers would suggest lead man rather than support, but even after Asif and Amir were gone, Pakistan turned to spin with such relish that Gul's 11 wickets in the 2011-12 clean sweep of England come across as a clerical error.

It all built into a tendency to dismiss him as a Test bowler, dimmed by comparison to those he bowled with, not shiny enough otherwise. And yet, to counter this, it feels necessary to point out that he is Pakistan's highest Test wicket-taker in the post-Ws era by some distance. Given how this modern history has played out, an equally key stat would be that no Pakistani fast bowler has played more Tests than him, although, having himself played only 47 of 80 Tests, that makes him a poster-boy for the fragility of the era.

To many, Umar Gul's 3-0-6-5 remains the best T20 spell ever•PA Images via Getty Images

No such caveats or qualms with a white ball. Gul at the 2007 World T20 was one of the first movers in the format that spoke of a different sport, with different specialisations, with players not bound by their functions elsewhere. Credit Shoaib Malik, Pakistan's captain then - and Pakistani history - for the tactic of Gul coming on from the 11th over and strangling the life out of the back-end of an innings.

But it needed Gul to execute and there was nobody better anywhere on the planet those first years. Just look at the table below, of bowlers in the last five overs of T20Is, until the end of 2012: highest dot-ball percentage, second-lowest economy, lowest average, most wickets. It's not even a contest.

| Bowler | Inns | Balls | Econ | Wkt | Ave | Dot% |

| Umar Gul | 45 | 472 | 7.34 | 46 | 12.56 | 38.61 |

| SL Malinga | 34 | 348 | 8.39 | 24 | 20.29 | 37.29 |

| SCJ Broad | 32 | 244 | 8.69 | 19 | 18.63 | 37.25 |

| TG Southee | 24 | 252 | 9.47 | 19 | 20.94 | 34.67 |

| DW Steyn | 22 | 204 | 7.29 | 16 | 15.50 | 34.21 |

| SR Watson | 21 | 170 | 7.48 | 14 | 15.14 | 33.20 |

| RJ Sidebottom | 15 | 152 | 7.89 | 13 | 15.38 | 32.58 |

| M Morkel | 22 | 189 | 8.38 | 12 | 22.00 | 31.76 |

| DJ Bravo | 16 | 122 | 10.08 | 12 | 17.07 | 31.20 |

| B Lee | 16 | 125 | 7.77 | 11 | 14.72 | 30.65 |

| AR Cusack | 12 | 120 | 9.25 | 11 | 16.80 | 30.17 |

| JW Dernbach | 14 | 150 | 8.96 | 10 | 22.40 | 30.00 |

| JDP Oram | 18 | 132 | 9.44 | 10 | 20.80 | 27.87 |

| TT Bresnan | 16 | 124 | 9.38 | 8 | 24.25 | 25.79 |

| KD Mills | 22 | 160 | 9.93 | 8 | 33.11 | 21.68 |

| KMDN Kulasekara | 18 | 143 | 11.28 | 7 | 38.42 | 20.63 |

Underpinning it was the yorker, which, if it didn't carry quite the spectacle of Lasith Malinga's, was arguably more effective. There was an unreal force around it, not least in how readily and accurately it was summoned. No moment in Pakistan's recent history should have felt as frayed as the 19th over of South Africa's chase in the 2009 World T20 semi-final. The entire country was under siege at the time, mostly from itself, and absolutely nothing about life in Pakistan felt secure. Neither would this moment have, except that it was Gul bowling it and at that precise point in time, the success of it was the one thing you could hang the fortunes of an entire country off. No way would Gul not pull this off and so he produced not only one of the format's most nerveless overs, but also one of the most inevitable.

ALSO READ: Top five - yorkerman Gul's greatest T20 hits

Penultimate overs were not - at least publicly - acknowledged as the thing they are now but Pakistan's use of Gul in that time suggests they knew it was. Until the end of 2012, Gul bowled that penultimate over nine times out of the 14 occasions that sides chased against him (and the final over, by comparison, four times).

That kind of excellence, it is good to hear, might be put to use in a coaching capacity. He has gained qualifications, is keen for more and though you can never be certain about such things, instinct says he will make a good, empathetic coach. And if he doesn't, then we'll still have this clean kaput of an exit, the completeness of a career with no lingering sense of unfulfillment. It's worth more than it sounds.

Osman Samiuddin is a senior editor at ESPNcricinfo