In Sydney they go feet first

Some of the most stylish, effective, nimble batsmen Australia has produced have the SCG to thank for their fleet-footed assurance against spin

Daniel Brettig

02-Jan-2012

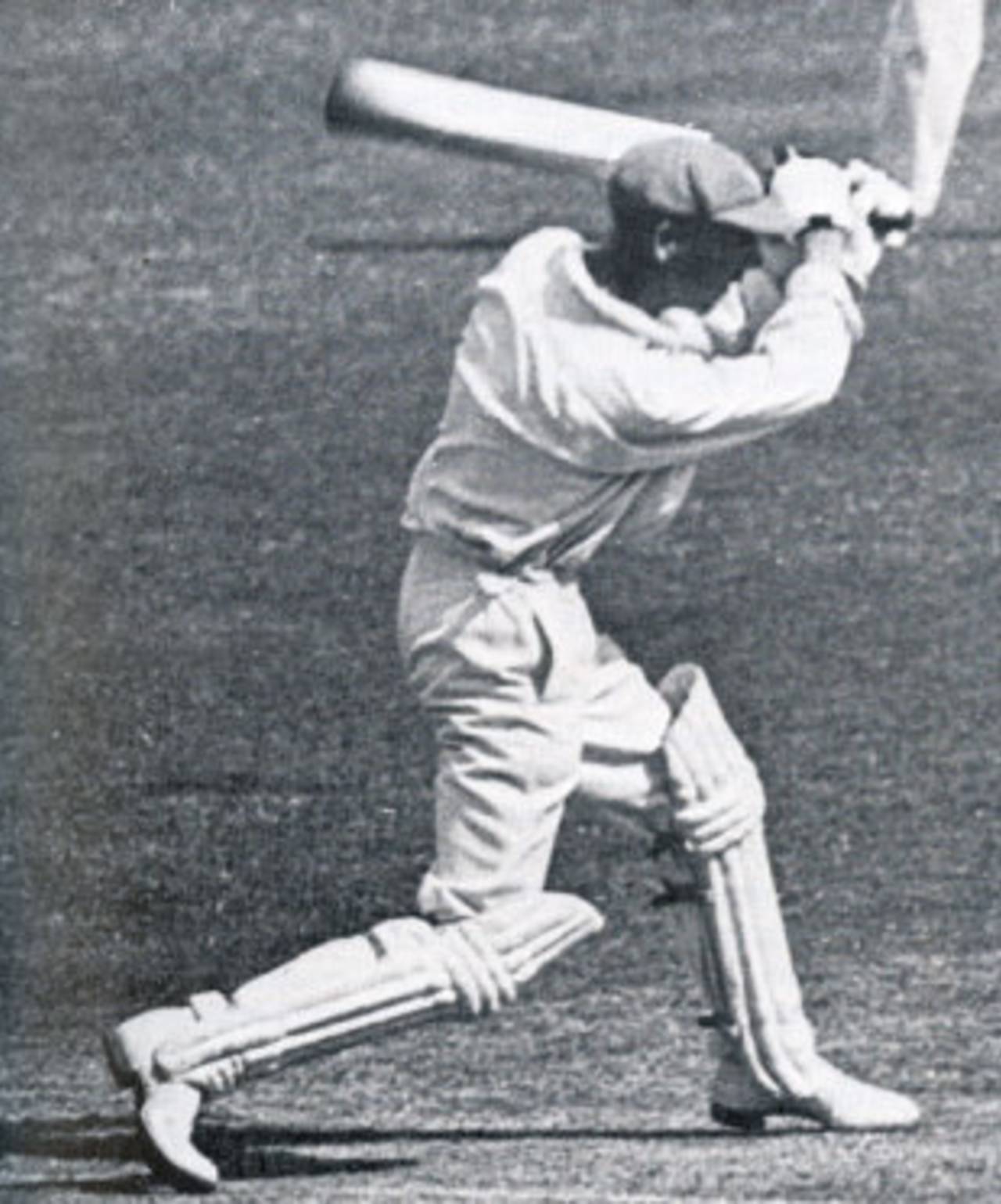

The beauty of Archie Jackson's method was often seen at the SCG • Getty Images

The difference is in the feet. Dancing, prancing, daredevilish and decisive, the footwork of the best batsmen schooled at the SCG says much about its singular blend of spinning pitches and swinging atmospherics. No other ground in Australia can boast of this balance, which has fostered generation upon generation of the most nimble strokemakers in the country.

Victor Trumper, Charlie Macartney, Alan Kippax, Archie Jackson, Don Bradman, Stan McCabe, Norman O'Neill, Doug Walters, Allan Border, Steve and Mark Waugh, Michael Slater, Michael Clarke. All have produced batting of great beauty, and ferocity. All have made life difficult for bowlers, of the spinning variety in particular. And all played their formative cricket at the SCG. Aesthetes have marvelled at their shots almost as much as bowlers have cursed them, and it is undeniable that the ground was greatly influential in the development of their batting style.

First, of course, there was Trumper. Born in Darlinghurst, of all the qualities that elevated him above his peers in what has so often been called the golden age, Trumper's batting on rain-affected pitches was the most striking. Sydney's knack for periods of rain and shine, dampening a wicket, then drying it deviously, gave him more practice at that now-extinct art than many contemporaries. When framed in George Beldam's enduring photograph, Trumper was batting in England. The daring drive, feet yards beyond the crease, eyes fixed on the ball, was repeated many a time in Sydney, though never quite captured so well by the camera.

In the years after Trumper's retirement and all too hasty death, Macartney, Kippax and Jackson maintained Sydney's penchant for batting beauty. Macartney's aggression extended to cutting the fastest bowlers off the stumps, his feet swift enough to make the stroke not merely possible but profitable. Kippax was also adept at the cut, but of the late and elegant variety, and he could hook with tremendous panache. He did it all with a gentlemanly air that was sadly out of place during the high tensions of the Bodyline series, and was never loved anywhere quite so much as in Sydney.

Jackson's tale is heavier, with the tragedy of an earlier death than even Trumper's, tuberculosis claiming him before his 24th birthday. Yet the sparkle of his batting briefly outshone Bradman, and drew comparison with the young Trumper for its audacity of footwork and beauty of method. Jackson only played one Test in Sydney, making 8 against West Indies in 1931. His health was failing then, but he played gloriously enough at the SCG for NSW to be part of the fabric of the ground.

At the outset of the 1930 tour of England, Jackson was rated above Bradman by many, but the notion did not last. Bradman's most storied first-class innings was his 452 against Queensland at the SCG the summer before the tour, and he would go on to enjoy success upon success there, causing crowds to flock when word spread through the city that he was batting. While it has been said there was less flourish than function about Bradman's batting, his feet were nimble as they come, and again benefited from the qualities of his home ground.

Bradman's company for much of the 452 was McCabe, to be the scorer of that most audacious, hooking 187 in the first Bodyline Test, at the SCG. Ray Robinson wrote of McCabe that he was the only batsman of his generation to dare attempt an innings so brazen as that. There were others in Nottingham and Johannesburg. During the Trent Bridge 232, McCabe's response to a patch of rough on a length was to skip out to meet the ball before it got there - those dancing feet again.

As a century of Sydney Test matches looms, the prospect of watching Clarke's agile movement towards the spinning, spitting ball keeps alive this most enviable batting lineage

After the war Norman O'Neill wore comparisons with his forebears somewhat uneasily, and was thought to have never quite lived up to his promise. But his feet kept him in command of spin bowlers more often than not, and foreshadowed the lively play of Walters as the 1960s wound down. Walters' aggression was often categorised by the term "bush technique", but his knack for getting right back into his crease to cuff the spinners was honed most effectively in Sydney. After Walters came Border, a batsman so often described as more a fighter than a flourisher, yet he too was adept against slow bowling, at least in part due to the lessons of his early days in NSW before Greg Chappell encouraged him north to Queensland.

It is worthwhile to ponder for a moment the batsmen who may have gained from more time at the SCG. How better might David Hookes have dealt with spin had he played half his matches at the ground? Would Ricky Ponting's initial visits to India have been quite so dire if he had batted more regularly in Sydney, where he now resides? It is no coincidence that Simon Katich, for one, became a more complete batsman once he had decided to call the SCG home, though his sidewards shuffle does not stand visual comparison with the kind of batting pursued here.

Plenty has been written about the Waugh twins and their contrasting styles, though sharing the same knack for using the width of the crease. Their stand of 190 against England at a packed SCG in the fifth Test of the 1998-99 Ashes was perhaps the perfect encapsulation of this, where they attacked an ensemble of pace and spin potent enough to top and tail the rest of the innings for a total of 322. Both drove exquisitely through cover, and Mark cut often to the square boundary. The partnership was the centrepiece of a day described as "cricket in excelsis", the Waughs playing a large part in making it so.

The second innings of the same match provided a superior example of Michael Slater's twinkle toes, first glimpsed by the world on the 1993 Ashes tour. Though England could curse a run-out not given due to a lack of the requisite smoking gun on television replays, Slater's shots on a wicket now turning treacherously were delightful in their dash. Three times he danced out to flay Peter Such for six. Shades of McCabe's method to bypass the rough in Nottingham.

At the time a poster of Slater adorned the bedroom wall of a teenaged Clarke, and he would carry those same dancing feet into the ranks of NSW and eventually Australia five years later. Spectators in Bangalore then, and Galle this year marvelled at Clarke's creativity in dealing with prancing spin on a bone-dry pitch. For Clarke, footwork is not only to jump out but also to jump back, his subcontinental reading of length a product of earlier days in the middle at the SCG, and also in the nets against the likes of Stuart MacGill. As a century of Sydney Test matches looms, the prospect of watching Clarke's agile movement towards the spinning, spitting ball keeps alive this most enviable batting lineage.

Daniel Brettig is an assistant editor at ESPNcricinfo