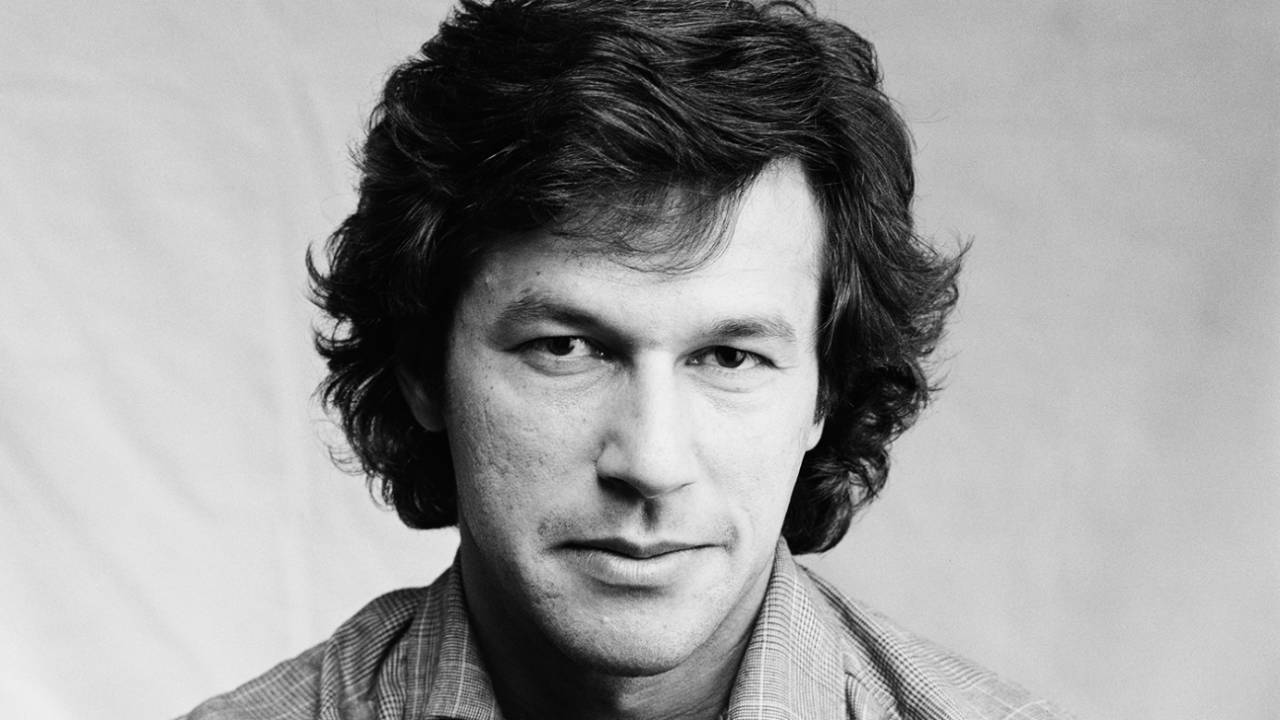

The original transformer

Imran was at the heart of shaping modern-day Pakistan cricket, and all we love about the team and their play can be traced back to him

Osman Samiuddin

31-Oct-2010

Imran Khan: the difference between a mediocre Pakistan and an exciting one • Getty Images

There lies, pop stars and politicians will tell you, great reward in transformation. Imran Khan, who hung out with the former and has become one of the latter, will tell you there lies greatness itself in transformation. This is the truth of his life and career. Many are conceived great but it can also be achieved by not necessarily being yourself as at conception, by changing, evolving, renovating.

The broad outline is that he went from being a good player to the finest one his country produced, and arguably the finest allrounder cricket has seen in a gathering not involving Sir Garry Sobers. Underpinning this was his real genius: an unbending commitment and a pig-headed focus, a blind devotion, really, to any given single cause - to better himself, to better his side, to better his country, to better the world.

So fierce is the single-mindedness that it has often become divisive, as with the 1992 World Cup-winning speech remembered so bitterly in Pakistan. So obsessed had he become with building the cancer hospital in memory of his mother, he didn't think to thank his own team or anyone else, speaking only of the project. That is the downside; the upside is that the cause drove him, and thus his team, to win the damn thing in the first place. And it isn't as if he was building something that would devour babies.

Details, though, are instructive.

His action, for example, when he began in the early 70s, looking like a misplaced Beatle with a mop top, had more windmills in it than Holland, and was as flat. Yet by 1982 it had become such a leaping study in the beauty and grace of the human form, all it needed was a catwalk; to half the human race it was a mating call. Visually it was as unrecognisable from his natural action as the Michael Jackson of 2008 was from the Michael Jackson of 1978. It came about after much consultation with greybeards and contemporaries and defiance of others, but above everything, from an inner voice that told him he could be far more than what he was.

His bowling itself underwent several recalibrations of pace, length, attitude and modes. When he began, he couldn't control big, booming inswingers of modest pace. But when cricket was gripped by a prolonged vogue of bouncers from the mid-70s on, Imran unthinkingly jumped in. When the run-up and rhythm were right, he was sharp, and he targeted heads with commendable indiscrimination.

But by the early 80s, a scholarship in Kerry Packer's World Series with the world's best to the good, and quicker still, he was hitting fuller lengths and ignoring the surface. He was swinging the new ball but more radically, the old; 40 wickets in the 1982-83 series against India in Pakistan was a mind-altering moment in fast bowling.

Then, post shin-injury, another face. The pace came down but the mind remained sharp; nearing 35 he took over 20 wickets in leading Pakistan to their first series win in England; a year later he took 23 in a three-Test series in the Caribbean; even at 37 he bowled a remarkable, long-forgotten two-wicket maiden last over of an ODI in Sydney, which Pakistan won by two runs.

Through this immense journey were the imprints of a few minds. Mike Procter and John Snow, Garth le Roux, the Kiwi John Parker, Sarfraz Nawaz, all chipped in, but overseeing it all at each step was Imran himself, pushing himself to whichever point and in whichever direction would bring him success.

Just imagine cricket's landscape in Pakistan without him. For sure the country would've been one of spinners and medium-pacers, no Wasim, Waqar, Zahid, Shoaib and Amir in sight

Nowhere more than in his batting did he inflict - and that really is the word - upon himself such stark transformation. The epiphany came in his very first Test as captain, until when he had been a free, reckless spirit in the lower order. A careless hook off Bob Willis ended a careless innings, and immediately he resolved to become more responsible; there was no harsher critic of Imran than Imran, not even slighted ex-players from Karachi. It didn't require the structural re-jigging of his bowling, for his batting was built on sounder, correct principles. In his head he had always been a batsman, even if in his blood he felt the flow of manlier pursuits. All it needed was for his mind to win. Obviously it did.

A solid 65, batting mostly with the tail in the second innings, was, in his words, a "watershed". The conclusion cannot be doubted; in his last 50 Tests after that, he averaged twice - nearly 52 - what he did before. He quintupled his century haul and quadrupled his fifties. More immeasurably, by career's end he was the calmest, most versatile influence on a batting line-up forever a wicket or two from panic.

Strictly speaking, these were all personal, isolated transformations. Even off the field he was chameleonesque, unrecognisable from the homesick 18-year-old who first went to England in 1971. A shy, introspective mama's boy, he became cricket's James Bond, as smooth on the field as away from it, as easy in whites with 10 sweats gathering round as in a tux with 10 royals, celebrities and the world's beauties. Some transformations cannot be matched: turning a productive day in the field with Javed Miandad, for example, into a heady evening with Mick Jagger.

But it was when he went from being a rebellion-happy superstar to captain that he initiated a process of change vastly bigger and beyond his own person.

Cricket in Pakistan probably would've become the most popular game anyway - and by the late 70s, hockey was a formidable match - but there was no bigger propellant than Imran's emergence. He had been at the very centre of Sydney 1976-77 - a triumph as significant as the Oval one of 1954 - in which was conceived modern-day Pakistan: a delicate, easily disturbed balance between fractiousness, indiscipline and supremely gifted athletes, between hostile fast bowlers and erratic batsmen. Thereafter, as the sport burst out of urban Pakistan, pouring out a hurl of talent, he remained at the centre, driving his side forth and, by default, shaping the game as it grew.

Imran's run-up: a mating call to half the world•PA Photos

If that sounds too much, just imagine cricket's landscape in Pakistan without him. Might not hockey be the national sport in name and spirit? For sure the country would have been one of spinners and medium-pacers, no Wasim, Waqar, Zahid, Shoaib and Amir in sight. There probably wouldn't be the modern attacking mores of their play, the gung-ho shot-making, the wicket-taking lengths and stump-hitting lines that were Imran commandments, developed as an antidote to the ennui he felt was drowning him on the English county circuit.

Without him they might still be the meek inheritors of nothing that they were in the 60s and early 70s. He was lucky to lead in a time of demographic change, so that for his players, partition and colonialisation were mere words in history books they hadn't read. But how well he harnessed these players into a new brave, defiant and unbowed visage, much of it still glimpsed today, even though it has since developed a schizoid moue. And almost certainly he was the difference between a mediocre, underperforming cricket nation and an excitable, winning one. Without Imran, Pakistan would not be as we know and love them.

This is what made him, to this writer at least, much more than his great all-round contemporaries. Maybe his peak as batsman and bowler didn't quite coincide to produce the starburst of Ian Botham early on (Imran did, by the way, average more than 50 with bat and less than 20 with ball in the last decade of his career). There wasn't the early precocity of Kapil Dev. Neither was he as calculatingly brilliant with ball as Richard Hadlee. But to be, at once, the best player in the side, the best leader of the side, and also the man to transform the entire sport in a country, that is some trump.

Now awaits the final, logical transformation. This is trickier, philanthropist to politician not being as straightforward a switch as it might appear. Perhaps he is better off sorting out the game first, for upon his own departure in 1992, just as he once wrote had happened on the retirement of AH Kardar, it was thrown to the wolves.

Osman Samiuddin is Pakistan editor of Cricinfo