Benaud, Swann and quantum theory

Why cricket, and spin bowling in particular, has plenty to do with advanced physics

Sue de Groot

29-Oct-2009

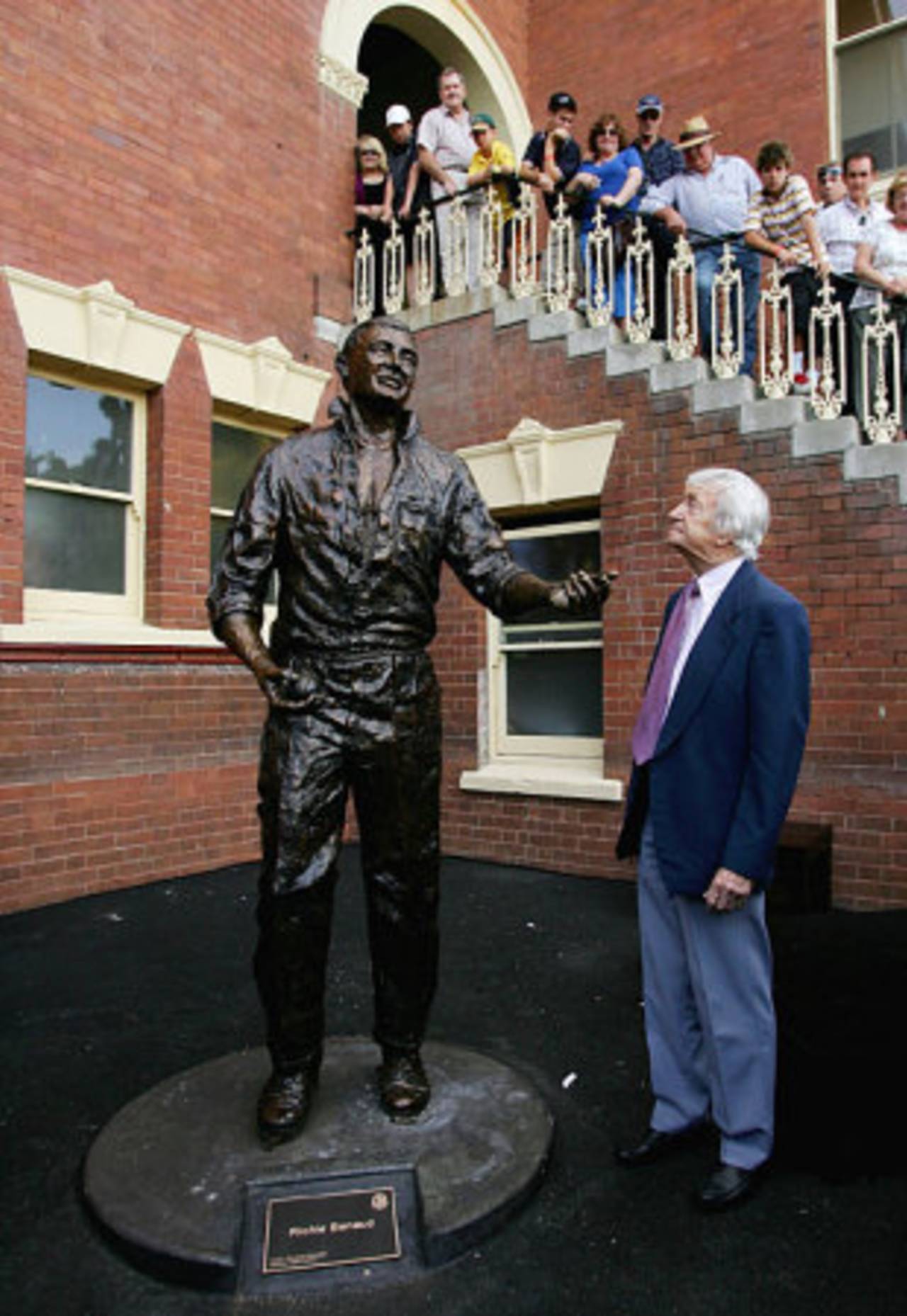

Richie Benaud takes lessons in oratory posture from a statue of himself • Getty Images

So here's my exam question: If all cricket matches were filmed, and if one had access to the infinite number of television channels on which all these matches were broadcast, would it be possible to watch cricket being played live, somewhere in the world, all the time?

Sadly, even if the conditions existed for perpetual cricket-watching, we fans would have to take a break now and then: to sleep, or earn a living, or sometimes read a book. Last week someone gave me one (a book, I mean) called We Need To Talk About Kelvin (not Kevin, Kelvin - as in the temperature scale).

This book is published by Faber and written by American cosmologist Marcus Chown. It is supposed to be about quantum theory, or "how familiar features of the world reveal profound truths about the ultimate nature of reality". Actually, it's about cricket.

Unusually for an American, Chown knows a lot about spin, and explains it with great clarity. "The spin of an electron behaves like a tiny compass needle," he says. "Actually, it behaves like a quantum compass needle. Unlike a familiar compass needle, it cannot align itself in any direction whatsoever, but only in two possible directions: along the direction of the field or against it."

That sounds like something Richie Benaud might have said. He was equally profound on several occasions. He once said, for instance, "His throw went absolutely nowhere near where it was going". See, it's not only scientists who can master the art of the non-statement.

But back to spin. There was a lot of talk, after the slow wrapping up of Shane Warne's career, about the slow death of spin bowling. Luckily for admirers of the art, it appears to be creeping back into fashion. Being an American, Chown may not yet have noticed this.

He says, "It turns out that microscopic particles such as photons possess a quantum property called 'spin'. In common with irreducible randomness, it has no analogue whatsoever in the everyday world."

Really? Tell that to Mushtaq Ahmed and Graeme Swann.

Or Donald Swann, for that matter, who knew a thing or two about elementary science. He and cohort Michael Flanders famously explained the first law of thermodynamics in just seven words: "Heat is work and work is heat."

Ever felt a cricket ball right after it's flown from a spinner's hand towards a distant bat? Nor have I, but I'm sure it would be hot, because it's been working. Which reminds me of that famous cricketing quote by William Herbert, first Earl of Pembroke, born in 1501. There must have been a shortage of bowlers in Herbert's time too, otherwise he wouldn't have ranted: "Out ye whores, to work, to work, ye whores, go spin!"

But back to quantum theory. "A photon has two possibilities open to it, says Chown. "It can behave as if it is corkscrewing in a clockwise manner about its direction of motion at a particular spin rate; or it can behave as if it is corkscrewing in an anticlockwise manner at the same rate."

Does that mean, with the right measuring device, the tactics of Swann and other spinners, like the lovely Johan Botha, might become entirely predictable and therefore harmless? Thanks to irreducible randomness, and thankfully for the future of spin, it seems not.

"It is impossible to predict for certain which way the photon will be spinning, even in principle," says Chown. "All we can know is that there is a 50 percent chance that when we detect the photon, we will find it spinning clockwise, and a 50 percent chance we will find it spinning anticlockwise."

Again I am reminded of Richie Benaud. "That slow-motion replay doesn't show how fast the ball was travelling," he said.

Incidentally Chown's previous book was called Quantum Theory Cannot Hurt You. Tell that to anyone facing an Anil Kumble delivery.

Sue de Groot is a Johannesburg-based journalist, columnist and television scriptwriter