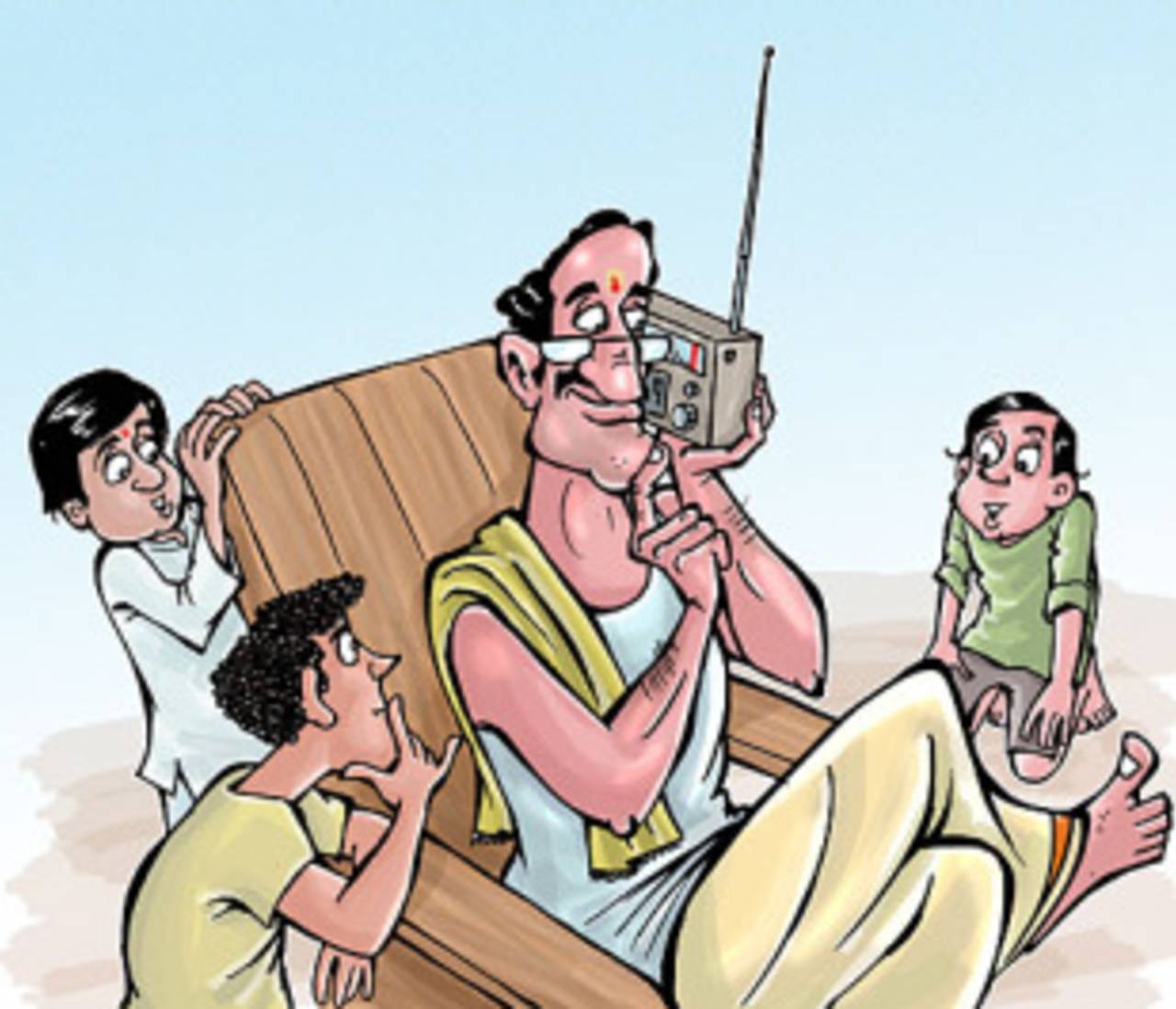

Ears glued to the cricket

In the years following India's independence, many fans' link to the game was the radio, usually owned by the English-speaking, all-knowing man of the town

Krish Ashok

Feb 14, 2010, 3:03 AM

Satish Acharya

The generation of Indian cricket fans whose lives straddled the British Raj and the Indian one is a unique lot. One would think that, when it came to picking a cricket team to support, the freedom movement would have impelled them to wear the tricolour on their sleeves with pride, but that wasn't the case. Down south, from where my parents come, the 1950s and 60s bred a distinctive bunch of cricket loyalists.

GS Sundaram was my grand uncle (one of many), and having served the British Raj as a privileged and educated member of an Indian society that was largely illiterate, he managed to achieve a neat bit of mental trickery that allowed him to claim: "I support India but I like English cricket."

Of course, back then Indian cricket was the equivalent of the Wright brothers' 1901 glider, while England was more an Airbus A380, so that helped. Everyone knew it was futile supporting India in a match against England, so by the 1950s it was politically correct to admire English cricket while admitting that India had some distance to cover before they could compete as equals.

It also helped that he lived in a hamlet near the southern tip of India, far away from politics and jingoism, and was the only man in the village with a radio. That confers a kind of power.

His Philips valve radio, the crystal ball that gave him his powers, could barely pick up the BBC, but static or not, GS was Moses. He held court when Ken Barrington unleashed crisp cover-drives and Colin Cowdrey leaned into an on-drive. He translated crackling bits of commentary into expressions like "splendid shot" and "wonderful flick o' the wrists", as young kids - my father among them - sat enthralled by the vivid (and often entirely made-up) cricket imagery he painted.

Like most from the radio era, he would often let ears become eyes, reprimanding Ted Dexter for needlessly chasing one wide outside the off stump, and demonstrating to his willing wards the right way to defend off the back foot. Barrington was, as far as he was concerned, the greatest batsman in the world. Ken was poetry, and GS would imagine his favourite poet, Keats, writing an ode to the square-drive, while he daydreamed about daffodils growing in Xanadu and Kubla Khan singing the rhyme of the ancient mariner.

He could afford to mix things up a bit. English literature was both mandatory and mostly inaccessible in India back then. Just being able to speak English put one on a pedestal so high that people rarely cared for the content of your speech. When his wife scolded him for spending his time fantasising about Sir Colin's majestic straight drives at times he ought to have been at work, he would respond with Shakespeare and ask if Mrs GS could hold a candle to the ethereal beauty of Desdemona. GS was an Anglophile but a harmless one.

Things became more difficult when Mr Sobers et al started to showcase to the world glimpses of what would eventually become the Caribbean juggernaut of the 80s. GS had to make some choices then. Would Peter May and Dexter still rule his cricketing heart, or would he have to start supporting West Indies? The colour of his skin eventually prevailed and he made an exception. When Rohan Kanhai faced Fred Trueman, he prayed for half-volleys. He also expounded on the evils of slavery to the kids gathered around his radio.

When Rohan Kanhai faced Fred Trueman, he prayed for half-volleys. He also expounded on the evils of slavery to the kids gathered around his radio

But Barrington continued to be his hero. If somebody was silly enough to make a careless remark about how Neil Harvey was really the better batsman, the radio would be switched off and the offending party removed from the premises. If Ken edged one to first slip, the radio would be switched off and the kids sent out so he could recover from his disappointment privately. Given the rarity of Test matches in those times, every garbled, static-filled "splendid shot" from the willow of Barrington was a rare thing, a treasure to be cherished.

Cricket was (and mostly still is) for most Indians a prohibitively expensive game to play. The village my father hailed from had a cricket association that would scrounge around to be able to afford their quota of two cricket balls (which cost Rs. 3 each, in the 50s) each month. Batsmen would be requested to avoid hitting the ball into the nearby river, as that tended to cause unplanned budgetary overdrafts. The leather balls themselves arrived all the way from England, and lasted about 10 days worth of cricket each. When a few over-enthusiastic improvisers indulged in a few too many agricultural heaves into the river, it was benefactors like Sundaram who coughed up the rupees and annas to buy more equipment.

It was common for batsmen to wear a pad on just the front leg, so that overall wear and tear on gear was kept down to a minimum. Indians from that era were well versed in the art of jugaad, of making do, but for some reason no one wanted to skimp when it came to the gentleman's game. Scorebooks would be procured from afar, and a good one-rupee coin used for the toss (not just any four- or eight-anna coin), and whites were mandatory.

Cricket was a ritual. Its arcane rules, the paraphernalia and the sheer minutiae involved in every game, all amounted to practically a religious experience for my father's generation. For conservative, religious and finicky gentlemen like my grand uncle, the rules of the game bore a similarity to the Vedas.

GS Sundaram, Bachelor of Arts, Gopalasamudram, Tamil Nadu, India, passed away well before innovations like limited-overs cricket reared their heads. I suspect he might not have enjoyed them. He lived his life in a more leisurely era, one that never considered time worth saving. He never ever watched a game of Test cricket in his life, and yet he managed to instill an intense passion for cricket in my father's generation. They, on the other hand, had an easier time getting us excited about cricket. They just had to switch on the TV.

Krish Ashok is an IT consultant, columnist and humourist who blogs at http://krishashok.wordpress.com